The SeaDoc Society’s goal to ensure the survival of ocean species in the inland waters of the Pacific Northwest faces quite a challenge thanks to robust economic success in the region.

This marine research nonprofit, a program of the UC Davis Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center and based on Orcas Island, focuses on finding science-based solutions for preserving the health of marine animals in the area known as the Salish Sea.

Some of the species’ biggest challenges come from humans. Seattle, whose port is situated on the Puget Sound, gains more than 1,100 new residents each week, making it one of the fastest growing metropolitan areas in the United States. Technology-based companies like Amazon, Boeing and Microsoft have solidified the Pacific Northwest as a hub for the tech industry, meaning the population boom can be expected to continue.

Across the Canadian border, British Columbia’s big city, Vancouver, is also positioning itself as a burgeoning region for technology, digital entertainment and green economy, attracting talented people and capital for growth.

The Salish Sea, which stretches from Olympia, Washington, up to the Campbell River in British Columbia, is far from immune to the effects of the people who call the area home. Some species are impacted so much so, in fact, that their very existence is under threat.

Learn about four species suffering human-caused plights, and how the SeaDoc Society is assisting in the effort to save them through science and education.

Southern resident killer whales

Southern resident killer whales, estimated at only 78 in total and considered an endangered species, face a number of challenges in the Salish Sea. These iconic beauties feed primarily on salmon, especially chinook, which have been dramatically overharvested, making it hard for the whales to find food. Meanwhile, the noise from boat engines (large ships, fishing boats and even whale-watching boats) hinders their ability to communicate and echolocate to find food. Increased noise actually forces them to vocalize more slowly and loudly, just like a human trying to communicate in a noisy room.

“They live in an acoustic world,” said SeaDoc Society Science Director Joe Gaydos. “They navigate and find food with their ears, but noise caused by boat traffic can inhibit their ability to effectively do that.”

Toxins have also been found in high concentrations in killer whales’ blubber. “These are legacy chemicals that humans have dumped into the ecosystem,” according to Gaydos. “They are persistent chemicals, so they remain in the sea for a very long time.” Those chemicals can depress killer whales’ immune systems, making them more susceptible to diseases.

Taking a One Health approach, SeaDoc has helped illuminate the role noise, food scarcity and disease play in killer whale deaths. For instance, SeaDoc helped author a standardized necropsy protocol that will ensure scientists glean all information each time a whale strands.

Salmon

The threats that chinook, a primary food source for killer whales, and four other species of salmon face can be divided into “four H’s,” all of which SeaDoc is studying:

- Habitat: Salmon are being threatened by destruction of the rivers and streams.

- Harvest: Overharvest of salmon is affecting their long-term survival.

- Hatcheries: Simply putting hatchery fish into the wild is not a solution. For genetic reasons, they don’t survive and thrive like wild fish.

- Hydropower: Building dams for electricity has blocked salmon-bearing rivers and streams, greatly impacting their ability to leave these rivers after being born, or return up them to spawn (reproduce).

Pinto abalone

After centuries of overharvesting, pinto abalone (also known as northern abalone) populations have dropped to less than 10 percent of 1978 levels. The existing population is aging without being replaced by younger individuals.

Existing, but not being able to reproduce, means pinto abalone are considered functionally extinct, and even closure of their harvest has not resulted in a rebound. Because too few are left in the wild to reproduce successfully, SeaDoc and other scientists are actively trying to recover them through tightly targeted projects involving hatcheries, genetic analysis for breeding stock, study of techniques for placing newly human-reared abalone into wild habitats and an assessment of the most successful habitat types for release.

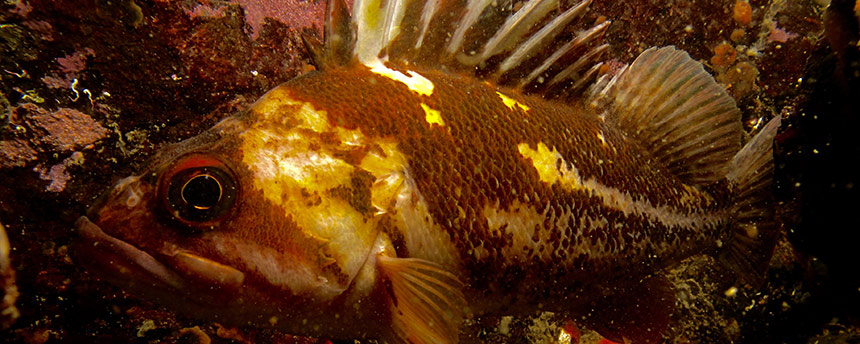

Rockfish

Like salmon and pinto abalone, multiple species of rockfish have been overharvested. They’re easy to catch, and they taste delicious, which is a recipe for disaster when humans are around.

Since the mid-’60s, the Salish Sea’s overall rockfish population crashed by 70 percent. The yelloweye, Boccaccio and canary rockfish are, in fact, endangered species.

Rockfish are a long-lived species (some live more than 100 years), and the biggest, fattest, oldest females produce more offspring than the young ones, so recovery of this slow-to-reproduce species is an uphill battle that will take time.

SeaDoc has funded and conducted numerous research projects on rockfish and rockfish recovery, many of which can be found in NOAA Fisheries’ Draft Rockfish Recovery Plan. The plan offers about 45 recommendations, including deeper research into rockfishes’ critical life stages, accidental bycatch and derelict fishing gear. The draft also addresses water-quality problems like persistent pollutants, low oxygen levels and other habitat issues.

All of these issues are challenging on several levels, and human impacts will persist regardless of the recovery work that’s done. However, whether it’s helping to get a species listed as threatened or formalizing necropsy protocols for killer whale strandings, the SeaDoc Society and other organizations are having an impact through the work they do. And the good news? SeaDoc has big plans to keep it going into the future.

Justin Cox is content marketing manager for the UC Davis One Health Institute and the Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center. He has a passion for storytelling about animals, people and the environment.