Your eye movements can show that the elements of a memory are in place even when you cannot consciously recall it or when you get it wrong, according to a new study from the UC Davis Center for Neuroscience. The findings, published Sept. 10 in the journal Neuron, could have several practical applications.

It has been known for some time that a part of the brain called the hippocampus is necessary for the conscious recall of memories, but Debbie Hannula, a postdoctoral researcher at UC Davis, and Charan Ranganath, associate professor of psychology, addressed the controversial question of whether the hippocampus can support memories even when people are unaware of them.

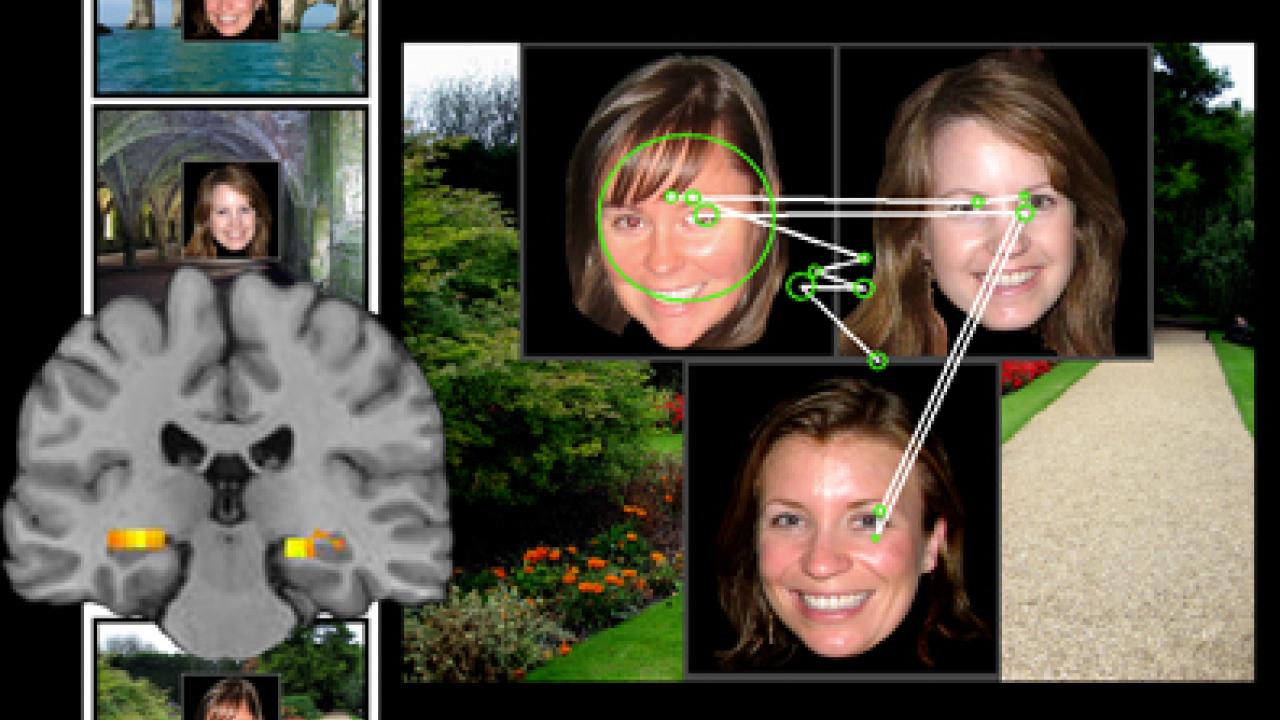

Hannula and Ranganath tracked the eye movements and scanned brain activity of volunteers using a functional MRI (fMRI) machine while they performed a simple memory test. The volunteers were briefly shown a scene, then a face superimposed on the scene. To test their recall, they were shown the same scene again, but with three faces on it, and asked which one they associated with the scene.

Previous work conducted by Hannula and her colleagues showed that the eyes move to the correct face before the volunteer is aware of recalling the memory. In the new experiments, the hippocampus lit up with activity seconds before the eyes fixated on the correct face, even when participants failed to explicitly recall it.

“The signal in the hippocampus was closely tied to how long people spent looking at the right face,” Ranganath said. “So even when your conscious memory is wrong, the eyes (and the hippocampus) may have it.” Ranganath said.

The fMRI images also showed more activity in another part of the brain, the prefrontal cortex, when memories were correctly recalled. The scans showed that communication between the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex was increased when people accurately recalled the face.

“We think that conscious memory comes from communication between the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and other parts of the brain,” Ranganath said. “But the hippocampus may be able to support memories, even when you can’t recall them.”

The eye-movement technique could have a range of uses. For example, it could be used to look for evidence of memories in people who are unable or unwilling to consciously recall them, to study

hippocampal function in patients or young children, and in studies aimed at developing new drugs to improve memory function, Ranganath said.

Media Resources

Dave Jones, Dateline, 530-752-6556, dljones@ucdavis.edu