Quick Summary

- Refugees’ purchases benefit local and national economies of host country

- Cash aid has greater economic impact than in-kind food aid

- Economic benefits exceed amount of donated aid

Refugees are often considered an economic burden for the countries that take them in, but a new study conducted by UC Davis with the United Nations World Food Program indicates that refugees receiving aid — especially in the form of cash — can give their host country’s economy a substantial boost.

The researchers found that these economic benefits significantly exceeded the amount of the donated aid.

The findings come as refugee numbers around the world are growing. In 2015, an estimated 15.1 million people were displaced from Syria and other locations around the world due to civil conflict or natural disaster, reaching a 20-year high, according to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees.

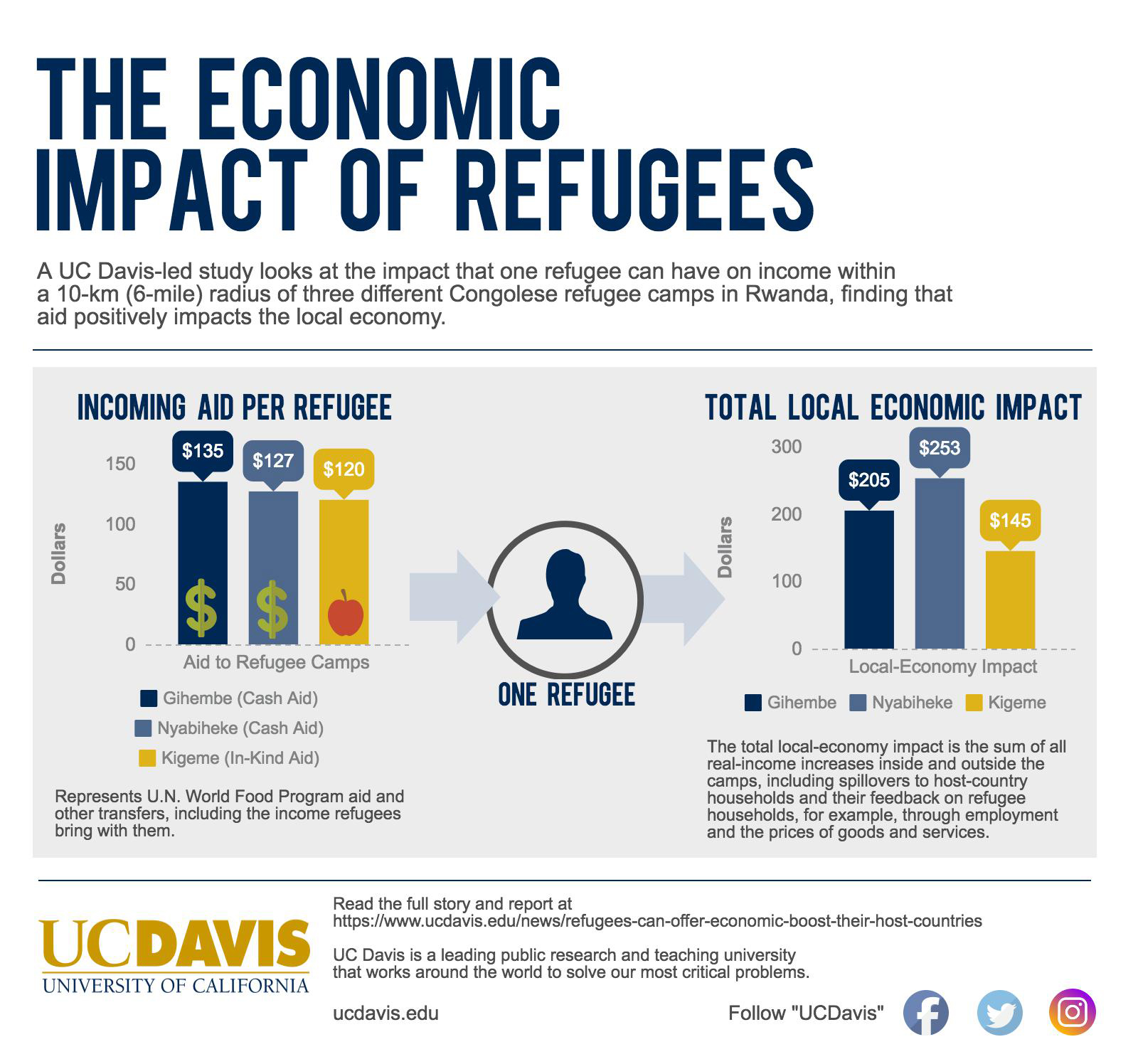

The new study, published online today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, examined the economic impact of three camps in Rwanda, housing refugees from the Congo. In two of the camps, refugees received aid from the United Nations World Food Program in the form of cash, while in the third camp the refugees received the same value of aid but in donated food.

The researchers used economic modeling methods, based on local surveys, to simulate the impact of the refugees on the host-country economy within a 10 km (6 mile) radius of the three refugee camps. They found that cash aid to the refugees had a greater positive impact on the host nation’s economy than did in-kind food aid.

“The findings of this study run contrary to the popular perception that refugees are helpless and dependent on food aid,” said J. Edward Taylor, the study’s lead author and a UC Davis professor of agricultural and resource economics.

“Our data support recent studies suggesting that although refugees have undergone forced migration and are often living in destitute conditions, they still are productive and can interact with their host country’s economy in positive ways,” Taylor said.

Local impact of cash aid in two refugee camps

In the two cash-aid camps, each adult refugee received an annual amount of $120 and $126, respectively, transferred to accounts linked to cell phones provided by the World Food Program. The researchers found that each additional adult refugee in either of those two camps increased the annual real income in the local area by $204 and $253, respectively. This was equivalent to 63 percent and 96 percent increases, created by each refugee in the two cash-aid camps, for the average per-capita income of Rwandan households neighboring the camps.

Most of that monetary “spillover” into the surrounding economy occurred when individuals and businesses within the camps purchased goods and services from businesses and households outside of the refugee camps, the researchers reported.

Refugee households inside the camps accounted for 5.5 percent of the total income within the 10 km radius of the three camps. And, 17.3 percent of the surveyed businesses outside of the camps reported that their main customers were refugees living in the camps.

Local demand increased incomes nationally

Looking beyond the immediate area, the researchers found that the demand and spending generated locally by the refugees also raised the overall incomes and spending levels for the host country, Rwanda.

Each refugee in the two cash-aid camps boosted annual trade between the local economy and the rest of Rwanda by $49 and $55, the researchers reported.

In-kind food aid had less economic impact

The economic impacts were smaller in the camp whose refugee residents received in-kind food aid rather than cash aid. In that camp, the refugees were given allotments of maize, beans, cooking oil and salt, designed to meet their minimum calorie requirements.

The researchers found that 89 percent of the refugee households in that camp sold part or all of their food allotments outside of the camp. Overall, food items totaling one-fifth of the value of the distributed food aid were eventually sold, often for significantly less than the local retail price.

This practice diversified refugees’ diets, by providing them with cash to buy a variety of foods. But it reduced the value of the food aid to the refugees and, by increasing the local food supply, put downward pressure on food prices in the area. Local food producers found themselves competing with cheap foods that had been provided to the refugees as aid.

As a result, the economic impact of each refugee housed in the in-kind food aid camp was just $145, compared to $204 and $253 mentioned above for refugees in each of the two cash-aid camps.

And in-kind food aid resulted in only a $25 increase per refugee in annual trade between the local economy and Rwanda’s national economy, compared to $49 and $55 per refugee in each of the respective cash-aid camps.

Lessons for future refugee aid

Taylor and colleagues noted that resettlement of refugees varies greatly around the world, ranging from isolated camps to refugee communities that are well integrated with host-country economies. The researchers suggest that their findings apply most directly to the more than 50 percent of United Nations-supported refugees who live in camps. The vast majority of refugees (86 percent) are hosted by developing countries.

“Our findings indicate that when refugees in these camps are given the opportunity to interact with the economy around them, they can create positive income spillovers for the host-country households and businesses,” Taylor said, noting that the Congolese refugees in Rwanda appeared to generate significantly more income than the cash aid they received.

“These findings suggest that a shift from in-kind to cash aid could provide greater economic benefits for the countries that are hosting refugees, if local farmers and traders are able to meet the higher food demand,” he said.

Collaborators and funding

Other researchers on this study were Mohamad Alloush, Anubhab Gupta and Ruben Irvin Rojas Valdes, all of UC Davis; Mateusz J. Filipski of the International Food Policy Research Institute in Washington, D.C.; and Ernesto Gonzalez-Estrada of the United Nations World Food Program, Kenya.

Funding for the study was provided by the United Nations World Food Program and the UC Davis Migration Research Cluster.

Media Resources

J. Edward Taylor, Agricultural and Resource Economics, 530-564-0443, taylor@primal.ucdavis.edu

Pat Bailey, News and Media Relations, 530-219-9640, pjbailey@ucdavis.edu