Nearly half of all arm amputees choose not to use their prosthesis, despite improvements in technology. Prosthetic devices can be too difficult to operate, unintuitive, and don’t allow amputees to sense pressure or temperature. At UC Davis, engineers, neuroscientists and surgeons are collaborating to solve this problem. In this episode of Unfold, we look at how the combination of surgery and machine learning is making life easier for amputees.

In this episode:

- Jonathon Schofield, assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, College of Engineering

- Wilsaan Joiner, neuroscientist and professor in the Department of Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior, College of Biological Sciences

- Andrew Li, assistant professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery, UC Davis Health

- Clifford Pereira, associate professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery, UC Davis Health

- Laduan Smedley, certified prosthetist-orthotist and biomedical engineer, UC Davis Health

- Fehran Maher, certified prosthetist-orthotist, UC Davis Health

- David Brockman, retired firefighter, hand amputee with prosthesis

See related in-depth multimedia story on this topic.

Transcript

Transcriptions may contain errors.

Amy Quinton

David Brockman is a retired fire captain with CalFire. He lives in Gridley, California, a rural community an hour north of Sacramento. About three years ago, a friend of his asked him to dispose of some fireworks. David agreed to help.

David Brockman

I didn't want to throw in the trash can because you know, goes to the dump and somebody runs over it. And so, I decided to light it instead of soaking in a tub of soapy water and dissolving it and tearing it apart. But instead of it doing what it was supposed to do, it detonated it in my hand. It was it was bad choice and bad luck crossed paths.

Amy Quinton

He was flown to UC Davis Health in Sacramento, where surgeons determined they couldn’t save his hand. They amputated from the wrist down. David then had a choice, learn to live without his hand, or learn to use a prosthesis or artificial hand. He chose the latter.

David Brockman

Because I was right-handed, and I lost my right hand. So, I had to relearn how to use my prosthetic as my right hand as well as learn how to do things left-handed where I needed more than just the hook. Because that's all I have right now is just the prosthetic hook.

Amy Quinton

His prosthesis is a simple mechanical hook and harness device that's been on the market for several decades. The harness around his shoulders keeps a carbon fiber prosthetic sleeve attached to his forearm.

David Brockman

On the end of that is a steel hook. And the hook has two fingers to it that open and close by me physically moving a cable that is attached to it and by me manipulating either my my arm by pushing out or manipulating my left shoulder, it pulls on a cable, which opens and closes the hook.

Amy Quinton

David also has another prosthetic device, a high tech one called a myoelectric. It works by using electrical signals from the muscles in his forearm.

David Brockman

I have that one and I think I've only worn it like twice or three times because one it's uncomfortable and two, it's not functionally, it doesn't function well. It's more aesthetics. It looks nice, it'll open and close. But and I not wearing a harness it just sits on my arm. But to do what I am very physical and be outside working in the yard, raking, doing things like that it doesn't work.

Amy Quinton

David is trying a new myoelectric prosthesis that he hopes will work better. He hasn't given up wearing one, but many amputees do, despite the improved technology. One recent study found that 44% of arm amputees reject or abandon their device entirely. UC Davis surgeons and engineers are collaborating to solve this problem. In this episode of Unfold, we look at how the combination of surgery and machine learning is making life easier for amputees. Coming to you from UC Davis.

Marianne Russ Sharp

and UC Davis Health,

Amy Quinton

this is Unfold, a podcast that breaks down complicated problems and unfolds curiosity driven research. I'm Amy Quinton

Marianne Russ Sharp

and I'm Marianne Russ Sharp. Not too long ago, the standard surgery for an amputee could still leave patients in a lot of pain.

Amy Quinton

Hand and plastic surgeon Andrew Li, with UC Davis Health, says that's because surgeons would have to cut bone muscle and nerves to remove a limb.

Andrew Li

Usually, nerves were either buried in muscle or buried in soft tissue. Sometimes they would bury it in bone to allow the nerves not to grow towards the surface of the skin and create a sensitive nerve end.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Unfortunately, even burying those nerve endings doesn't help some amputees, many patients still develop what are called neuromas. It's like a live wire.

Andrew Li

You can end up having the nerves grow and form a scar ball at the kind of that interface where it's buried. I have heard of cases where the muscle itself became extremely sensitive, where moving that muscle created kind of electrical sensations and discomfort.

Marianne Russ Sharp

And you've probably heard of phantom pain. That's when an amputee can feel cramps or burning where the amputated limb used to be. As many as 2 million amputees in the US suffer from chronic pain. Some have to rely on medications, including opioids.

Amy Quinton

And as you might imagine, the pain from neuromas can also make wearing a prosthetic device impossible. And even amputees that don't experience pain can sometimes have difficulty wearing a prosthesis because they're difficult to operate. I talked to Laduan Smedley about this. He's a certified prosthetist orthotist at UC Davis Health.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Meaning he fits amputees with new artificial limbs.

Amy Quinton

Right and he's also a biomedical engineer. He says the more high- tech devices, the myoelectric ones, aren't exactly easy to use. For a hand amputee, Smedley says some work by attaching two electrodes to the forearm and amputees would have to use those forearm muscles to move the hand in different ways.

Laduan Smedley

And they would have to memorize kind of these patterns of flexion and extension or co-contraction to operate the hand. So, I describe it somewhat like Morse code to where you have to memorize these sequences to do different gestures with a hand.

Marianne Russ Sharp

That does not sound intuitive.

Amy Quinton

Now it's not. And Jonathan Schofield agreed. He's an assistant professor in the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department at UC Davis, who is researching this problem.

Jonathon Schofield

Right now, even though there's amazing dexterous devices that can move in all sorts of ways and look similar and operate similar to an intact limb, being able to tell all of that robotic system, how to move and what you want it to do is really where a big barrier is currently in the field.

Amy Quinton

Schofield says some of the newer myoelectric devices are so complex, they require amputees to use smartphones to select the grasp they want to use.

Marianne Russ Sharp

So, they have to use an app?

Amy Quinton

Yeah, and he says, that's not exactly intuitive either.

Jonathon Schofield

When I think about opening and closing my intact hand, I'm not pulling out my iPhone to do that or trying to pulse and contract and, you know, isolate specific muscle groups to open and close my hands to make a pinching motion.

Marianne Russ Sharp

How far away are we from being able to improve these systems?

Amy Quinton

Not very far. Actually. We'll get into that in a bit. It's important to note though, that surgeons really helped pave the way to make myoelectric devices easier to use.

Marianne Russ Sharp

That's right, surgeons, not engineers.

Amy Quinton

Yeah, several years ago, surgeons began operating on amputees using a procedure called targeted muscle reinnervation or TMR.

Marianne Russ Sharp

The surgery reroutes amputated nerves to other nerves and residual muscles. This is instead of burying the nerve endings in muscle or bone.

Amy Quinton

UC Davis plastic surgeon Clifford Pereira says by doing this called reinnervating, they are restoring function to that muscle. Signals from the brain that once controlled the now missing hand, are now able to control the new muscles. These new muscles are smart enough to do what the old muscles used to.

Clifford Pereira

We can then convert the dumb muscle into a smarter muscle. Because based on what the patient thought of, say, making a fist or opening their fingers or bending, bending the wrist, or bending the elbow, different parts of the muscle will contract and using that the prosthetic could be a little bit more intuitive.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Ultimately, then amputees don't have to learn how to control the device using muscles they wouldn't normally use for that action. They don't have to learn a complicated sort of Morse code technique.

Amy Quinton

Right.

Marianne Russ Sharp

That's very cool.

Amy Quinton

What's cooler is the secondary effect of this procedure says hand surgeon Andrew Li.

Andrew Li

It was originally done to increase the number of muscle signals that a patient could generate after an amputation. So, they there could be more degrees of control of a prosthetic device. And a kind of an unintended benefit was that those patients also tended to have reduced phantom limb pain and neuroma pain as well.

Marianne Russ Sharp

So reduced pain was just completely by accident?

Amy Quinton

Yeah, although it kind of makes sense giving a cut nerve ending something to do.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Right. The procedure should be great for lowering the number of amputees who need medication to relieve pain then

Amy Quinton

Yeah, exactly. Also, I read that if surgeons can transfer multiple nerves amputees can have even more mobility, more fluid motion, and simultaneous control of joints. One amputee who had the surgery is David Brockman.

Marianne Russ Sharp

He's the one who's still using his hook and harness device.

Amy Quinton

Yeah, when I interviewed him the first time he was, so I caught up with him again as he was getting fitted for a brand-new prosthesis, a smarter prosthesis.

Laduan Smedley

So today, we have your prosthetic hand attached to the clear socket. We have the electrodes built into it.

Amy Quinton

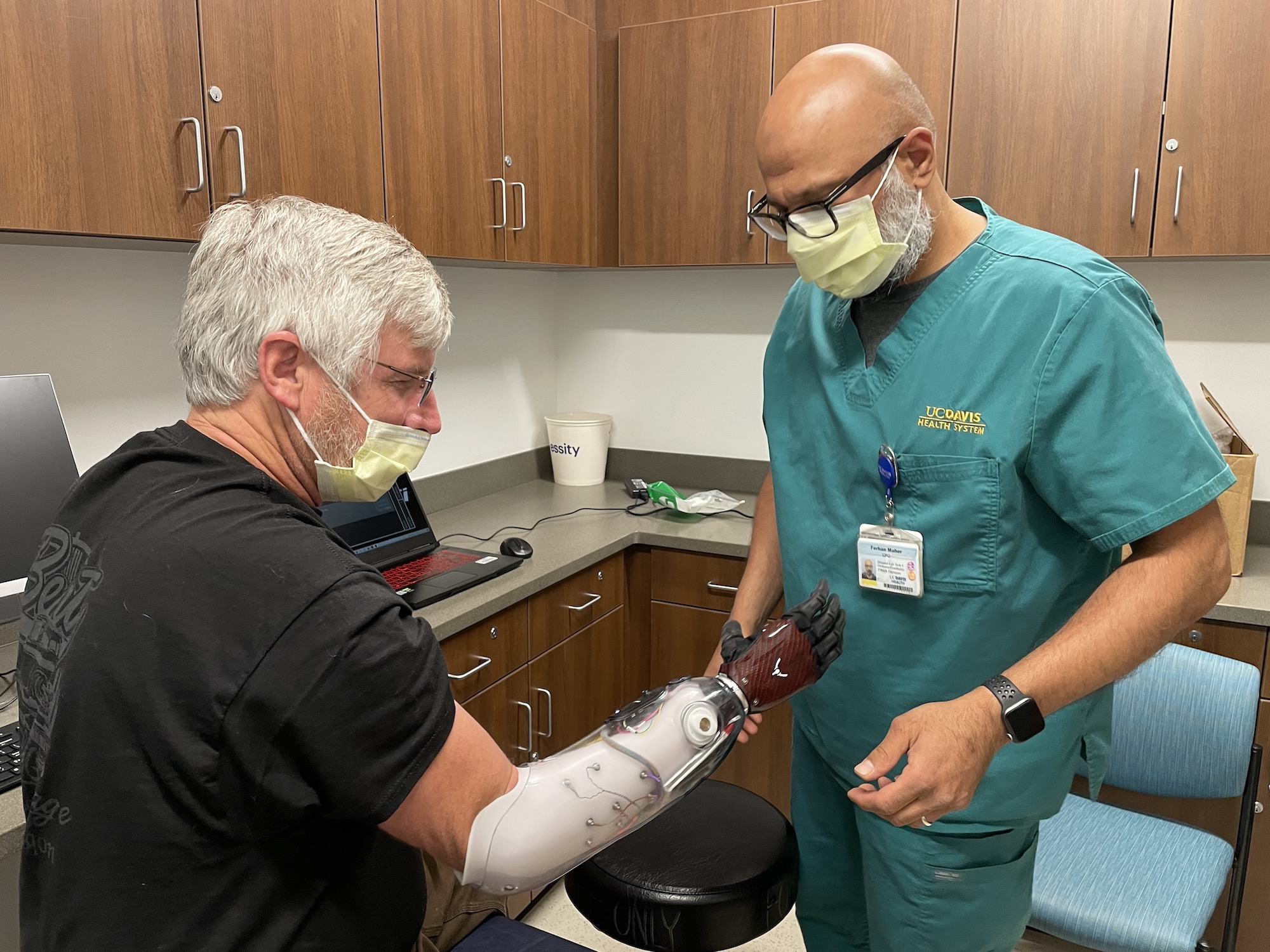

Laduan Smedley and Fehran Maher both UC Davis Health prosthetists are about to fit David Brockman with a new myoelectric device. They're using a long sleeve that's made out of a crinkly parachute material to help slide David's forearm into the clear plastic socket of his prosthesis.

David Brockman

So, this is just like putting a stocking on to help it slide in.

Fehran Maher

This is one of those wind vanes sliding things Yeah, it's gonna help get your tissue in there.

Amy Quinton

They need the fit to be tight, so it doesn't fall off but not so tight that it pinches.

Fehran Maher

Now that your elbow is in there is it still biting you?

David Brockman

Yeah, right there you can see you can see the white spot right there.

Fehran Maher

Yeah, what about the elbow back there?

David Brockman

The elbow? I can feel it. It's it would be uncomfortable if I wore it all day. Right now it doesn't hurt but I can definitely feel it

Amy Quinton

After Maher make some adjustments, Smedley brings out a robotic hand to attach to the socket. It looks like a black glove and the fingers can move independently, just like the hand in the movie The Terminator. Smedley uses an app to test out the movement first.

Laduan Smedley

So, I'm doing this from the app.

David Brockman

Gotcha. Yeah, All the fingers wiggling.

Amy Quinton

David says this new myoelectric device was considered experimental when he first got his hand amputated. So, his insurance company wouldn't pay for it. He's excited that that's now changed.

David Brockman

They actually call it a bionic hand. It's a working functional hand, it has five fingers. It's got like 13 sensors built into the sleeve. And it works off a muscle reactions in my arm. And so, when I twitch my thumb nerve, which is still there, the prosthetic senses that and the thumb will move.

Amy Quinton

But first Maher says the prosthesis has to learn how to read these signals.

Fehran Maher

We're going to train the system to understand the patterns that he's firing with his muscles inside. Before it was like you had to extend or flex to cause certain open close reactions to happen. Now what we're trying to do is read everything and ask the computer to kind of sort out, does that look like an open signal or does that look like a closed signal?

Amy Quinton

David says the new prosthetic device will make a huge difference in his life.

David Brockman

They said with practice, I'll be able to pick up like coins off the ground again, things like that. For me, I love the outdoors. This is a dream come true because I'll actually be able to grab my fishing pole and reel and grab things again instead of trying to hook it and it keeps slipping off.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Amy, it sounds like the combination of surgery and these smarter prosthetic devices will be life changing for some amputees.

Amy Quinton

That's the goal. But as you might imagine, there are still a lot of things these prosthetic devices can't do well or can't do at all.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Like what?

Amy Quinton

Well, there are still issues with speed, lag time and movements that aren't very smooth. Even David's new prosthesis requires an app so we can select a grasp, although he can use several simultaneously.

Marianne Russ Sharp

I guess you can't feel through a prosthetic hand either so you probably can't tell if something's hot or cold or what about like pressure.

Amy Quinton

Yeah, Smedley mentioned that this was an issue with one of his arm amputees that has a young daughter.

Laduan Smedley

He wants to know that when he's holding his child's hand that he's not going to squeeze it. You know, imagine one of his young daughters, you know, already seeing his dad kind of wearing this prosthetic arm and maybe being a little weirded out by it. And then it's just, you know, squeezes her hand too hard, it would be somewhat traumatizing for her. So that's always a concern of his.

Amy Quinton

Our surgeons, engineers and neurobiologists are collaborating to address these issues. The ultimate goal is the concept of prosthetic embodiment.

Marianne Russ Sharp

I imagine that means they want these devices to really mimic a biological limb.

Amy Quinton

Yeah, and to do so without the increased complexity. UC Davis neuroscientist Wilsaan Joiner is part of this collaboration and studies how humans learn and control movement.

Wilsaan Joiner

So, there's certain properties that we know about motor control. And a lot of those properties are not reflected in your ability to control prosthetics. And right there, that's a problem. Because if you if you're not utilizing what's the natural abilities, or at least the natural infrastructure of our motor system, to basically control an external device like that, it's probably going to be incredibly difficult and non-intuitive to learn how to do.

Amy Quinton

So, he an engineer Jonathan Schofield are trying to make these devices feel and operate much more naturally.

Jonathon Schofield

And that's what we're trying to fill that gap is we're trying to say, how can we allow someone to think about making a pinching motion or think about making a fist with their missing hand and just let the prosthetic limb do that for them?

Marianne Russ Sharp

So where do they start?

Amy Quinton

They're first examining muscle firing patterns of amputees who have had TMR surgery, including David Brockman. One way of doing that is through electromyography, which records the muscles electrical activity

Jonathon Schofield

I'm gonna ask you to think about closing and opening your hand. Starting the trial now.

Amy Quinton

This is inside a UC Davis lab where the research is taking place. And Schofield has attached electrodes to David Brockman's forearm.

Jonathon Schofield

Pinch

Jonathon Schofield

We were measuring the muscle activity in that limb, and we were asking him to think about moving his missing hand into various positions. So, pinches, fists, moving his wrists up and down and rotating his wrists.

David Brockman

They would tell me point your finger even though I don't have a finger anymore, point your finger and their machine would read that muscle movement or that muscle thought.

Jonathon Schofield

What we were trying to figure out is can we recognize patterns in his muscle activity when he tries to do those things with his missing hand?

Amy Quinton

Marianne electromyography is one way to examine how David's muscles are firing, but sometimes it doesn't give you the full picture. Sometimes it picks up electrical signals from other muscles. So, scientists are also using ultrasound to detect those signals as well.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Right, ultrasound uses sound waves to produce images.

Amy Quinton

Yeah, and if you contract your muscle, it becomes denser. So, it bounces back more sound. This also allows scientists to see even deeper muscles, and they're taking that dataset and using machine learning.

Jonathon Schofield

So, we're leveraging artificial intelligence machine learning algorithms that are looking at the muscles that remain in that person's residual limb. And it's looking at that activity. And it's learning what that activity looks like when they wanted to pinch or make a fist or make a pointing motion.

Marianne Russ Sharp

So, they're making a prosthesis way more intuitive by using both ultrasound and electromyography

Amy Quinton

and AI.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Now, that's cool. One of the other problems you mentioned was that amputees still can't feel their prosthetic devices, so they have no way to gauge temperature or even pressure. Is there a way to address that problem?

Amy Quinton

Yeah, let's take temperature for example. It's important, you're going to want to feel a handshake or feel touch. You're also going to want to know if your prosthetic hand is on fire. Right?

Marianne Russ Sharp

Right.

Amy Quinton

The problem is sensory nerves are also cut during amputation. But surgeon Clifford Pereira says surgeons may be able to do with sensory nerves what they did with motor nerves in the targeted muscle reinnervation.

Clifford Pereira

The way we are trying to do that is through something called TSR or targeted sensory reinnervation. So the idea is you take the same cut nerves, or the amputated nerves, and take the sensory fibers and connect them to sensory nerves in the overlying skin.

Amy Quinton

Then if the artificial hand is touched or gets hot, it would send that signal to the skin of the amputee.

Marianne Russ Sharp

That is very cool. Or very hot, as the case may be. It sounds like what they're doing is really integrating prosthetic devices into the body almost like a human machine.

Amy Quinton

Well, it's interesting that you mentioned integration. So let me ask you, if you close your eyes and wave your hand, do you know where your hand is and how fast it's moving?

Marianne Russ Sharp

Okay let me try. Yes, definitely.

Amy Quinton

Your brain can’t perceive that action with a with a prosthetic device, unless of course, you literally integrate it into your limb or body, which is the next step in smart prosthetics.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Wait, what?

Amy Quinton

It's called osseointegration. Here's the way surgeon Andrew Li described it.

Andrew Li

Which is making the prosthetic essentially heel into the bone and become a weight bearing structure.

Amy Quinton

Bionic?

Andrew Li

A bionic arm.

Amy Quinton

Marianne, this sounded to me just like something really futuristic.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Or like something from the bionic man. Right?

Amy Quinton

You mean the 1970s show the $6 Million Man?

TV Show Clip

Steve Austin will be that man better than he was before. Better, stronger, faster.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Yep. Okay, but You're kidding, right? Because this doesn't give amputees super strength. We're not really creating bionic people.

Amy Quinton

No, of course not. Li went on to explain this better before I jumped to ridiculous conclusions.

Andrew Li

With osseointegration you can still take it off, but it's much more a solid component of your body that could potentially make things a lot more intuitive, a lot more natural, if you will, like picking up heavy things, doing pull ups potentially.

Amy Quinton

Osseointegrated implants for lower extremities are FDA approved and allow direct integration between bone and the surface of a prosthetic device.

Marianne Russ Sharp

So it feels a lot like part of your body.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Exactly.

Marianne Russ Sharp

We've unpacked a lot in this episode. But you can find even more on our website, including video of some of these prosthetic devices.

Amy Quinton

Yeah, and you can watch David Brockman's new myoelectric prosthetic hand and check out all of our episodes at ucdavis.edu/unfold. I'm Amy Quinton.

Marianne Russ Sharp

And I'm Marianne Russ Sharp.

Amy Quinton

Unfold is a production of UC Davis. Original music for Unfold comes from Damien Verrett and Curtis Jerome Haynes. Additional music comes from Blue Dot Sessions.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Did you know you can listen to Unfold on YouTube? Just search for Unfold, a UC Davis podcast and you can find all of our episodes from this season and previous seasons. What better way to listen to a podcast than to watch it?

Amy Quinton

If you liked this podcast, check out UC Davis's other podcasts, the Backdrop. It's a monthly interview program featuring conversations with UC Davis scholars and researchers working in the social sciences, humanities, arts, and culture. Hosted by public radio veteran Soterios Johnson, the conversations feature new work and expertise on a trending topic in the news, subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.