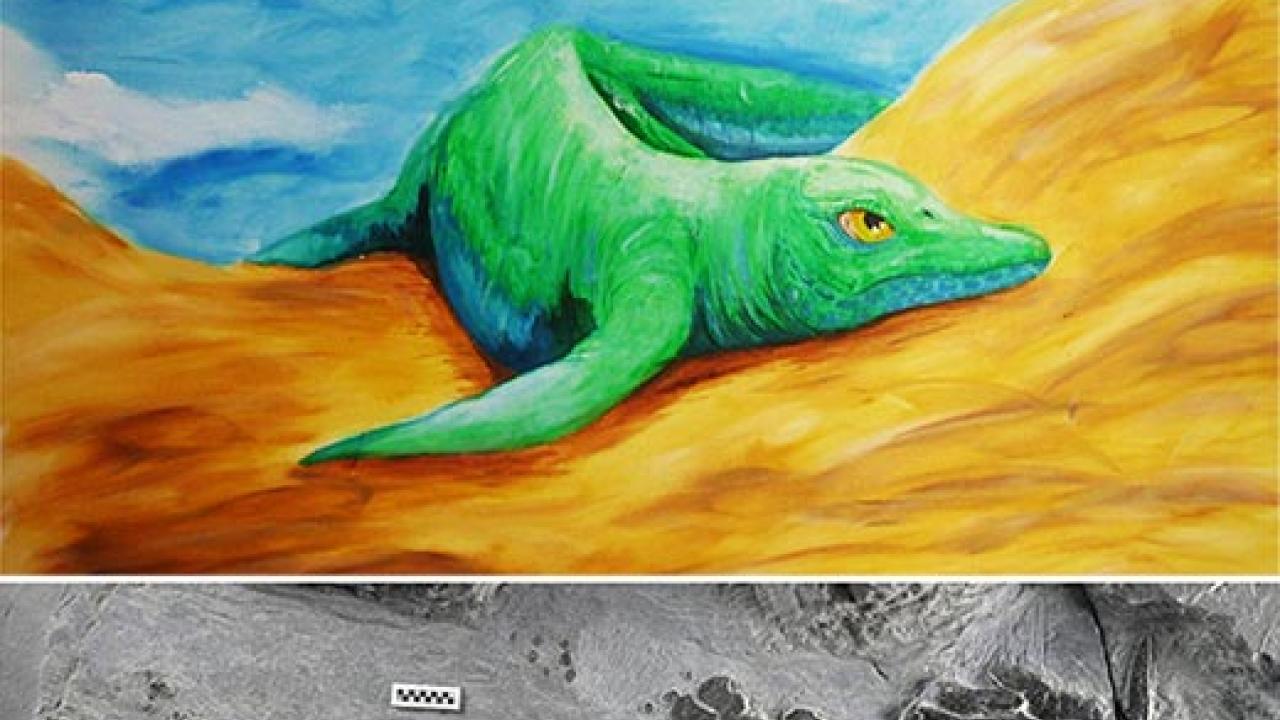

The first fossil of an amphibious ichthyosaur has been discovered in China by a team led by researchers at the University of California, Davis. The discovery is the first to link the dolphinlike ichthyosaur to its terrestrial ancestors, filling a gap in the fossil record. The fossil is described in a paper published in advance online Nov. 5 in the journal Nature.

The fossil represents a missing stage in the evolution of ichthyosaurs, marine reptiles from the Age of Dinosaurs about 250 million years ago. Until now, there were no fossils marking their transition from land to sea.

“But now we have this fossil showing the transition,” said lead author Ryosuke Motani, a professor in the UC Davis Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. “There’s nothing that prevents it from coming onto land.”

Motani and his colleagues discovered the fossil in China’s Anhui Province. About 248 million years old, it is from the Triassic period and measures roughly 1.5 feet long.

Unlike ichthyosaurs fully adapted to life at sea, this one had unusually large, flexible flippers that likely allowed for seal-like movement on land. It had flexible wrists, which are essential for crawling on the ground. Most ichthyosaurs have long, beak-like snouts, but the amphibious fossil shows a nose as short as that of land reptiles.

Its body also contains thicker bones than previously described ichthyosaurs. This is in keeping with the idea that most marine reptiles who transitioned from land first became heavier, for example with thicker bones, in order to swim through rough coastal waves before entering the deep sea.

The study’s implications go beyond evolutionary theory, Motani said. This animal lived about 4 million years after the worst mass extinction in Earth's history, 252 million years ago. Scientists have wondered how long it took for animals and plants to recover after such destruction, particularly since the extinction was associated with global warming.

“This was analogous to what might happen if the world gets warmer and warmer,” Motani said. “How long did it take before the globe was good enough for predators like this to reappear? In that world, many things became extinct, but it started something new. These reptiles came out during this recovery.”

In addition to UC Davis, the research team included scientists from Peking University, Anhui Geological Museum, Chinese Academy of Science, University of Milan and The Field Museum in Chicago.

The study received funding from the National Geographic Society, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education, and the Department of Land and Resource of Anhui Province.

Media Resources

Kat Kerlin, Research news (emphasis on environmental sciences), 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu

Ryosuke Motani, Earth and Planetary Sciences, 530-754-6284, rmotani@ucdavis.edu