I’d never so appreciated a date and a bottle of water until I spent a day earlier this month observing a day of Ramadan fasting — abstaining from all food or drink while the sun was up.

This year, Muslims observe the holy month of Ramadan from March 22 to Friday (April 21); the dates vary each year depending on the first sighting of the crescent moon. Each day ends with an iftar, or fast-breaking meal, like the one co-hosted by the Arab Student Union and the campus Police Department on April 7. When they asked me to attend, they also invited me to fast for the day, so I decided to try it out.

At exactly 7:36 p.m., I broke my fast with a sip of water and a date, both of which tasted incredible. I sat at my table at Putah Creek Lodge for what felt like a long time, taking small drinks of water and contemplating the bottle like it was some priceless artifact.

I was one of more than 100 people in attendance, most of whom, gathered on tarps outside to pray before eating dinner.

Building community

The event was the brainchild of core officer Tabbasum “Tabby” Malik ’19, who was a member of the Pakistani Student Association when he was an undergrad. He said he knew many Muslim students who observed Ramadan and got together at night to break their fasts, but usually just within their own clubs or groups. Members of the Pakistani Student Association often opted for late-night trips to IHOP, he said.

“There’s got to be a way for us to all work together,” he recalled thinking about two years ago. “We could have everybody together — that’s our whole goal here [at UC Davis], inclusion.”

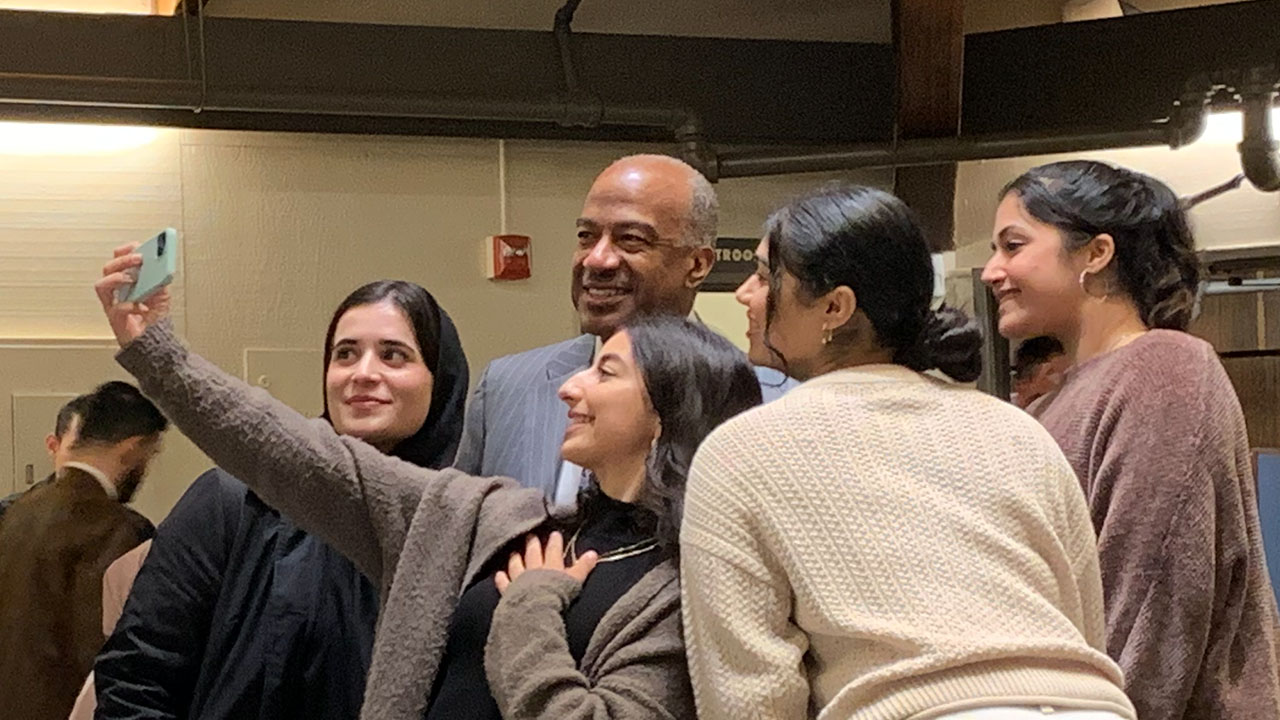

Other members of the Police Department — especially fellow core officers Ricky Lee and Joe Connors — were supportive of the idea, and they worked together with the Arab Student Union to host the iftar. Police Chief Joe Farrow and Chancellor Gary S. May were in attendance, shaking hands and posing for photos with attendees.

Lee fasted for the day, saying he wanted to learn more about what his partner of two years experiences every Ramadan.

A focus on charity

During Ramadan, the lunar month that marks the time period when the Quran began to be revealed to Prophet Muhammad, Muslims focus on acts of charity. Several student clubs and organizations donated gift baskets for a raffle at the event. The $350 in proceeds was donated to the Middle East Children’s Alliance, which supports initiatives like education for Syrian refugees, a music program for refugee children in Gaza, children’s books and literacy programs in Palestine and more.

I bought a $7 raffle ticket and won a movie-themed gift basket donated by the Afghan Student Association filled with candy, popcorn, a blanket and a Regal Cinemas gift card.

The drawing came after dinner, and buoyed by soup, rice and fried vegetables, I was feeling much more celebratory. I happily posed for a photo with other raffle winners.

Farah Mustafa, a sophomore wildlife conservation major who is the secretary of the Arab Student Union, said the event was about educating attendees about Ramadan in a town where iftars “aren’t super common,” and doing some good.

“Really, it’s just about giving back,” she said.

I wasn’t the only non-Muslim at the event, or even among the organizers, since the Arab Student Union isn’t a religious club.

Grace Hassanieh, a fourth-year nutrition science major and the club’s vice president, said she grew up in Saudi Arabia attending iftar events, even though she isn’t Muslim. She said it was an important event to host not only to provide education about Islam, but to provide some comfort to students.

“A lot of students are living away from their families,” Hassanieh said.

Throughout the process of the fast and iftar, I was reminded that I didn’t know anything about the reasons why Muslims fast for Ramadan, and that I wasn’t the only one.

When I told one friend that I was participating in a Ramadan fast, she replied, “I didn’t know you were Jewish!”

Physical and mental effects

I’ve fasted before, but never without water. Just the idea of the fast seemed daunting, and I sought out tips to help me succeed.

“I would suggest drinking plenty of water through the rest of today so you are hydrated … the no-water portion of the fast is often the most difficult,” Malik said by email the day before the iftar. “The times you often eat lunch will probably be the most difficult time as your body will want food. This would be a good time to take time to focus on something else that would be meaningful to you, or something you have been meaning to accomplish. During the fast, it is also a common practice to refrain [from] habits that you might have been meaning to alter.”

A colleague told me during a meeting to be sure to wake up before dawn and eat a big meal. This meal, a suhur, is a Ramadan custom, so I’m likely not the only person who was awake at 4 a.m. the day of the event (I had set my alarm for 4:30, but woke up early, perhaps because I was anxious of missing my window to eat).

Throughout the day, which I spent working from home, I experienced a wide range of sensations and emotions: I was hungry, of course — especially when I was making breakfast and dinner for my wife and our two kids. After walking past a glass of water a few times, I moved it to a different room so I could put it out of my mind. I had trouble focusing in a meeting I attended, and felt weak — especially around lunchtime, as Malik predicted.

But I also focused on finding the positive in challenges that day, and I found myself filled with gratitude to be fortunate enough to be in a situation where I can regularly spend so much time with our kids, who are 4 and 1 and changing rapidly.

Several attendees at the iftar asked how my fast had gone, and they confirmed something I felt throughout the day: It’s better to be busy so that you don’t dwell on your hunger or thirst.

“Now you know how we feel,” one attendee told me.

Muslims across UC Davis — faculty, staff and students — push through the effects of Ramadan each year.

“I'm tired because I have not eaten very well and I’m not drinking,” Mairaj Syed, an associate professor of religious studies, said in a recent interview with the UC Davis Humanities Institute’s Dialogic podcast. “I know my Muslim students are also very tired. They’re hungry. They’re probably not getting as much sleep as they would. I’m also the same way, and we’re also trying to meet all of our obligations.”

But as Malik’s email alluded, Ramadan isn’t just a physical test for followers of Islam.

“It’s training for what is coming, that’s the point of fasting,” Imam Ammar Shahin, religious director at the Islamic Center of Davis, told attendees at the Putah Creek Lodge event. He said during Ramadan, Muslims not only abstain from food, drink, smoking and sex — they are expected to avoid critical remarks, arguments or spreading rumors. Doing so prepares them to continue those good habits through the rest of the year, he said. “If you’re able to do it for one month, you can do it the rest of the year.”

In the same vein, if a Muslim sees a hungry person on the street, they should happily give up their own meal so that person can eat, he said.

“So what if you go hungry for a meal? You went hungry for a month,” Shahin said.

At the iftar, club members worked in the serving line and were insistent on sharing food with others. Meals were placed, unprompted, in front of guests like Chief Farrow and Chancellor May, and I saw attendees being urged to join the line to get food.

Malik said he was thrilled with the turnout, which spilled out of Putah Creek Lodge onto tables on the patio and lawn outside. He said he was looking forward to more events to further connect Aggies.

“We have so many opportunities and chances to bring people together,” he said.

Sign me up for the next one.

Media Resources

Cody Kitaura is a News and Media Relations Specialist in the Office of Strategic Communications, and can be reached by email or at 530-752-1932.