Quick Summary

- Cow embryonic stem cells may offer a better model for human stem cell therapies than using mice or rats

- Isolating cow embryonic stem cells will advance genetics in the cattle industry

- Efficient method could lead to ‘in vitro’ breeding, decreasing breed time in cattle

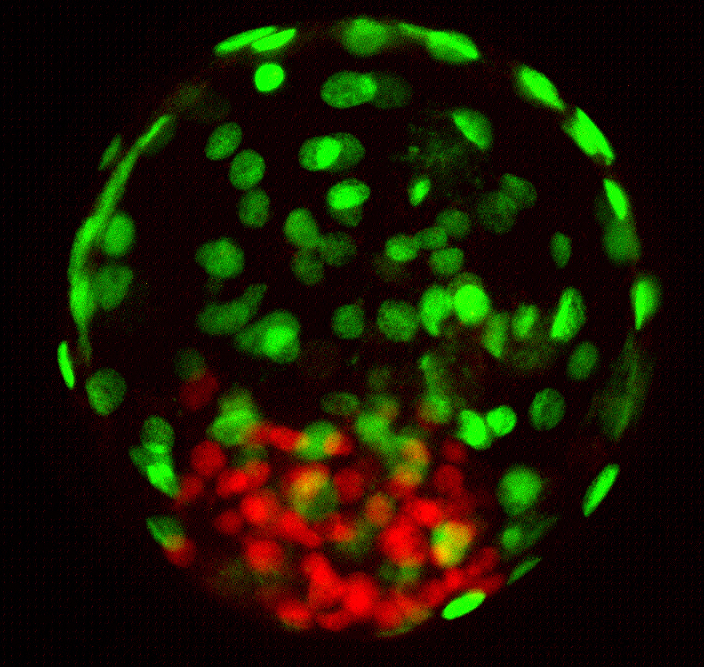

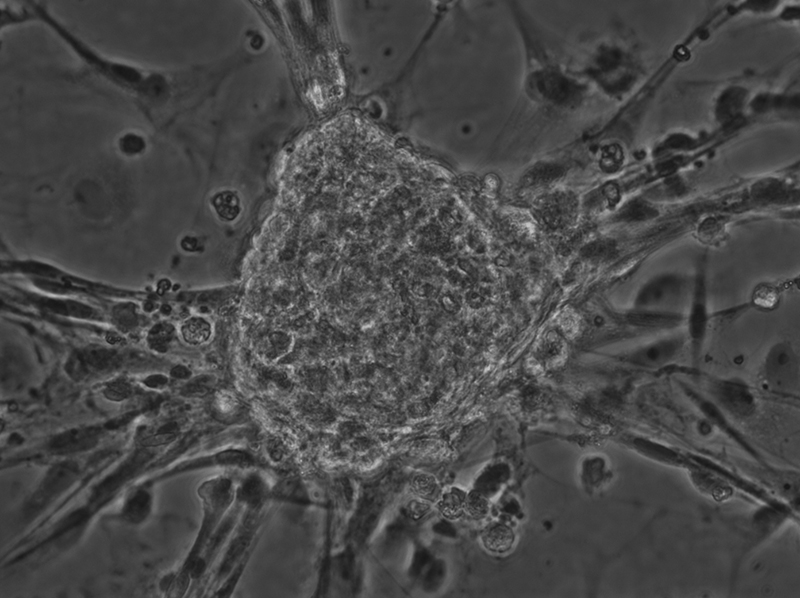

For more than 35 years, scientists have tried to isolate embryonic stem cells in cows without much success. Under the right conditions, embryonic stem cells can grow indefinitely and make any other cell type or tissue, which has huge implications for creating genetically superior cows.

In a study published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists at the University of California, Davis, were able to develop a new culture system that allows them to efficiently derive stem cells on almost every single attempt.

Producing embryonic stem cells from large livestock species like cattle is important for genetic testing, genome engineering and studying human disease. The cells may offer a better model for human stem cell therapies. Mice and rats are sometimes too small to demonstrate whether certain therapies will work on humans.

Breeding a better cow, faster

If researchers can generate gametes, or sperm and eggs cells, from the stem cell lines, the ramifications are profound. Such “in vitro” breeding could decrease the amount of time it takes to produce genetically superior cattle.

“That could revolutionize the way we do genetics by orders of magnitude,” said study author Pablo Ross, an associate professor in the Department of Animal Science at UC Davis’ College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

In just a few years, scientists could speed up the process of improving generations by decades. “In two and a half years, you could have a cow that would have taken you about 25 years to achieve. It will be like the cow of the future. It’s why we’re so excited about this,” said Ross.

The cow of the future could have more muscle, produce more milk, emit less methane, or more easily adapt to a warmer climate.

Ross envisions the findings helping the cattle industry become more sustainable. “Animals that are more efficient and have improved welfare, that may have more disease resistance is better for everyone,” said Ross.

Additional co-authors include Yanina Soledada Bogliotti, Marcela Vilarino, Delia Alba Soto, Rafael Vilar Sampaio with the UC Davis Department of Animal Science; Jun Wu, with the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center; Daiji Okamura with Kindai University; Cuiqing Zhong, Masahiro Sakurai, Keiichiro Suzuki and Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte with the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Media Resources

Amy Quinton, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-752-9843, amquinton@ucdavis.edu