Quick Summary

- DEET was more effective than Picaridin as a repellent

- Older mosquitoes were less sensitive to repellents

- Higher doses were best for dealing with older, infected mosquitoes

If you’re traveling to, or living in, a Zika virus-infested area, it’s far better to use the mosquito repellent DEET rather than Picaridin and to use higher doses of DEET because lower doses do not work well with older mosquitoes.

That’s the conclusion of a study by chemical ecologist and mosquito researcher Walter Leal, distinguished professor in molecular and cellular biology at the University of California, Davis, and his colleagues at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Recife, Brazil.

The work, funded by the National Institutes of Health, was published today in the journal Nature Scientific Reports. The researchers used mosquitoes originating from colonies reared by UC Davis medical entomologist Anthony Cornel and from colonies in Recife.

“We used assays to test the mosquitoes infected with the Zika virus,” Leal said, “and we asked whether the Zika infection affects mosquito response to repellents.”

Repellents compared

The researchers tested DEET and Picaridin, considered the top two mosquito repellents, because it was not known whether being infected with Zika virus would affect how mosquitoes react to repellents. Instead of human volunteers, a behavioral assay that mimics a human subject was used in the study.

“We discovered that DEET works better than Picaridin against the southern house mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus, and the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti, whether the mosquitoes were infected or not,” Leal said.

The researchers also found that old mosquitoes that already had a blood meal were less sensitive to repellents, most likely because of age, Leal said.

“Lower doses — normally used in commercial products — work well for young mosquitoes,” Leal said, “but the old ones are the dangerous ones because they may have had a blood meal infected with virus and there was enough time for the virus to replicate in the mosquito body.

“The bottom line: to prevent bites of infected mosquitoes, higher doses of repellent are needed,” he said. “The data suggest that 30 percent DEET should be used. Lower doses may repel young, nuisance mosquitoes, but not the dangerous, infected, old females.”

Collaborators and funding

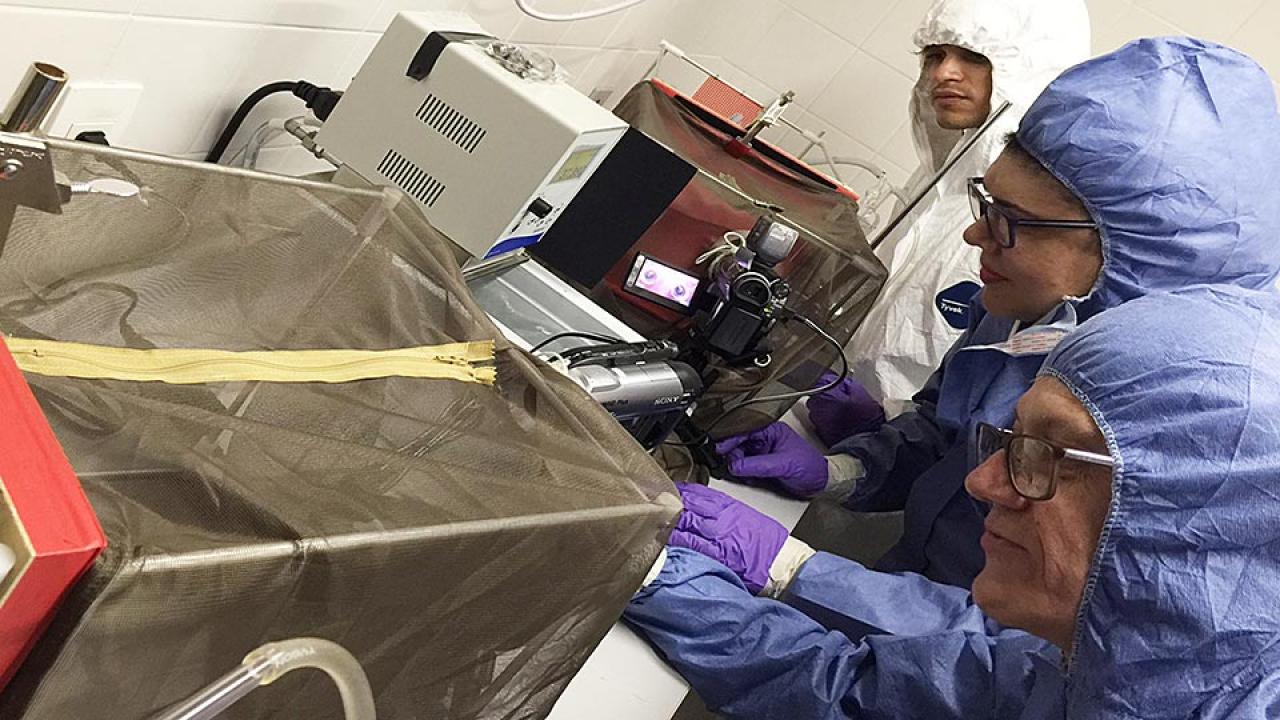

Leal, a native of Brazil, collaborates with Rosangela Barbosa and Constancia Ayres of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation. The work with infected mosquitoes was conducted at the Foundation’s labs in Brazil.

Other coauthors are: Fangfang Zeng and Kaiming Tan, UC Davis; and Rosângela M. R. Barbosa, Gabriel B. Faierstein, Marcelo H. S. Paiva, Duschinka R. D. Guedes, and Mônica M. Crespo, all of Brazil.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that people traveling to or living in areas with Zika virus outbreaks or epidemics adopt preventive measures, including the use of insect repellents, to reduce or eliminate mosquito bites.

Media Resources

Walter Leal, UC Davis Dept. of Molecular and Cellular Biology, 530-752-7755, wsleal@ucdavis.edu

Kathy Keatley Garvey, UC Davis Department of Entomology, 530-754-6894, kegarvey@ucdavis.edu

Pat Bailey, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-219-9640, pjbailey@ucdavis.edu