This is an excerpt of coverage by Caleb Hampton of The Davis Enterprise of this year's Campus Community Book Project author's talk. Reprinted by permission.

A LIVING MEMORIAL

The day of the author’s visit also featured the debut of “Gun Violence: Our National Narrative — A Living Memorial,” led by the students of Theatre for Social Change, advised by Margaret Kemp, associate professor of theatre and dance. See below for photos and more information.

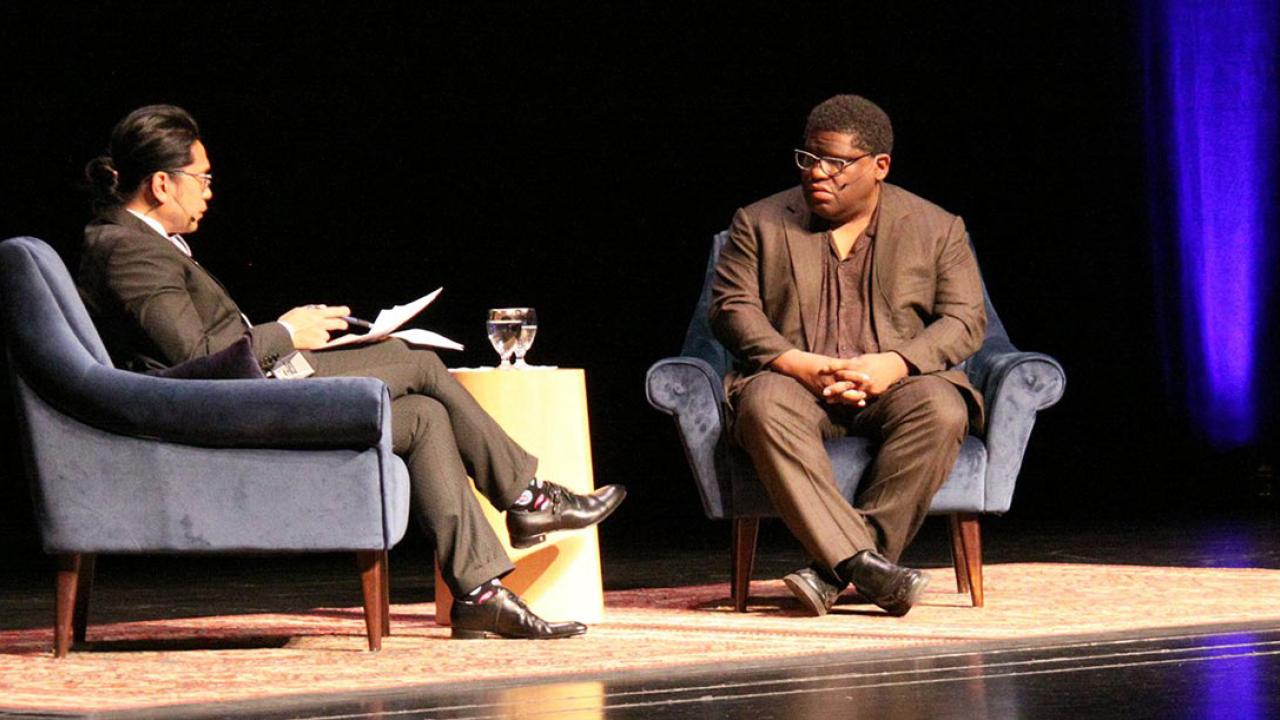

Campus Community Book Project author Gary Younge addressed a campus audience March 2 about his book Another Day in the Death of America, in which he chronicled the deaths of 10 children and teens in one day in 2013 — victims of gun violence.

“Society — pretty much every society — understands that we have a collective responsibility for children,” Younge said in his address to an audience of some 500 people in Jackson Hall at the Mondavi Center for the Performing Arts.

Of the 10 children profiled in the book, seven were black, two Latino and one white. More than a few were growing up in neighborhoods impacted by decades of housing discrimination, school segregation, and a combination of over-policing and under-investigating. “In many if not most instances black deaths such as these don’t count for an awful lot,” Younge wrote.

Failing our children

The bottom line, he said, is that when it comes to gun violence, America as a country is failing its children. “These kids have grown up with the narrative that they live in the greatest country on Earth and yet that country cannot or will not keep them safe,” he said.

To insulate ourselves from an uncomfortable reality, there are a number of narratives many of us choose to believe, Younge said.

In his book, he quotes a Facebook comment on a news article about one of the deaths: “I have two adult kiddos and there’s no way they would’ve been out walking streets after dark, and I always knew where they were. I do not blame the victims but all parents could do better.”

“That begs the question, first of all, when is a reasonable time for a child to get shot?” Younge asked. “Dusk? Is it after dusk? Is that what we’re saying? After 11 the shooting starts?”

Younge, who interviewed that victim’s family, said the Dallas teenager, Samuel Brightmon, had been drinking cocoa, playing card games and watching a movie with his mother, friend and sister and was shot for no discernible reason while walking his friend home a few blocks. “The worst thing that Samuel did that night was cheat at UNO,” Younge said.

The notion that “there were some people out there who had it coming,” Younge said, makes it easier for us to look away from the problem and shield ourselves from the thought that we might bear some burden of responsibility. “As long as you think bad parenting is the problem, why would you listen to calls for restraint?”

Because racist social and economic policies have skewed the demographics of those represented in gun violence statistics, the narrative that gun violence is solely a matter of personal responsibility is often also racialized. There is an idea that “the gun problem is a problem of deficient people with a deficient culture,” Younge said.

Toxic masculinity

If there is a cultural problem responsible for the gun violence seen in the U.S., Younge said, it has to do with pathologies around masculinity. “There is a lot of work to do in terms of how men respond to threat, to pressure, to humiliation,” he said.

These notions around masculinity are not particular to one subculture or even to the U.S., he said. What is particular to the U.S. is the wide availability of guns—and gun manufacturers who know they can profit by appealing to masculinity.

Much of the advertising by the National Rifle Association, or NRA, Younge said, plays on “the American narrative of homestead and rugged individualism.” Television advertisements and public speeches at massively attended NRA conventions often focus on fear and the need to defend oneself, family and property from a home intruder.

When he spoke with NRA members, Younge said, they would ask him, “Are you married? Do you have children? Imagine someone broke into your house. What are you gonna do? Call the police and wait for them to pick up your body or are you gonna stop and defend what’s yours and fight for your family?”

“On a very crucial level, this is absolute nonsense,” Younge said. That type of scenario seldom plays out in real life. The statistics tell us that we are most likely to be shot by someone we know, and often times — especially for women — that person is our spouse or partner.

“If the [NRA’s] story was consistent, they would say, ‘Are you married? Well watch out, ‘cause your wife might shoot you dead,’” Younge said.

While traveling around the United States reporting for the book, Younge was struck, he said, that few if any of the victims’ families blamed guns for the death of their loved ones.

“My understanding was that many people saw it a bit like traffic. If your child was run over, you wouldn’t say traffic is the issue,” Younge said. “No one is gonna say, well, you just have to get rid of traffic, because that would be impossible. And there was that sense with guns.”

A Living Memorial

In conjunction with this year’s Campus Community Book Project, UC Davis’ Theatre for Social Change envisioned a memorial to the lasting and far-reaching legacies of gun violence in the United States. The troupe invited community members to reflect on what resonates for them in thinking about gun violence: thoughts and memories; the challenges we face personally, politically, in our communities and across our country; and hopes and calls for action. Contributors wrote their reflections on tags, and the memorial’s creators affixed the tags to orange ribbons hanging from a metal structure. People attending the book project's author events March 2 had the opportunity to view the memorial at the Mondavi Center for the Performing Arts. The memorial also was on display at the UC Davis Equity Summit, March 10.

Media Resources

Caleb Hampton