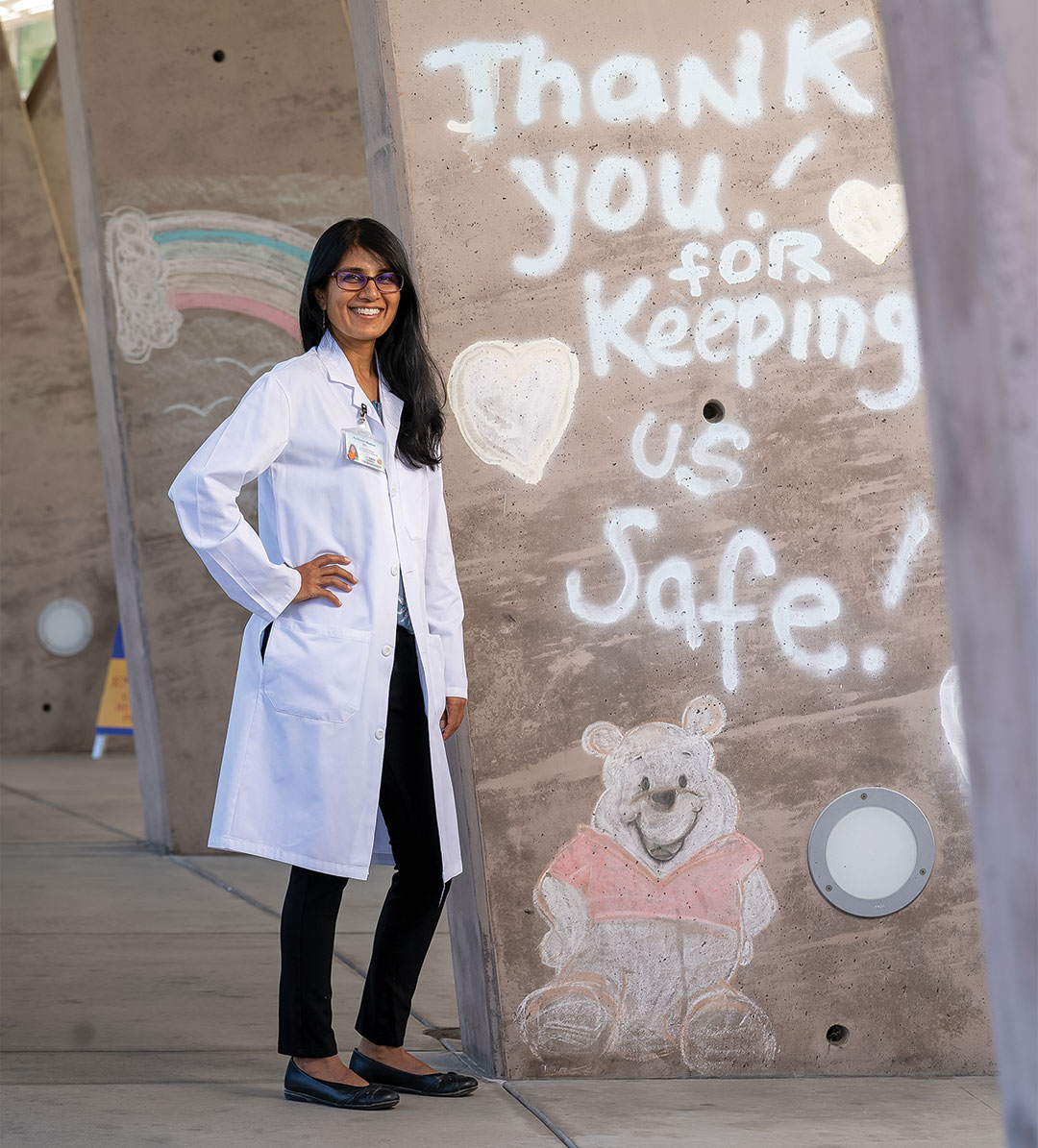

The Epidemiologist

Preparing a hospital and health care system for the coronavirus pandemic wasn’t like reinventing the wheel. It was like inventing a wheel.

That’s how Archana Maniar, M.D. ’00, who does double duty as an associate professor of internal medicine at UC Davis Health and head of infection control at the VA Northern California Healthcare System, described this spring.

“If I excavated my desk I could probably find what I was doing before COVID at the very bottom and since then it’s been overwhelmed by papers,” she said.

Before the pandemic hit, Maniar did things like monitor pneumonia infections among patients who are on ventilators, track flu activity and provide information about vaccines. Then COVID-19 hit and was “all consuming,” forcing Maniar and others to create policies for isolating patients, tracing potential exposures and protecting the health care workers at the dozen or so clinics and facilities that make up the Department of Veterans Affairs network in Northern California.

That network — dispersed over an area spanning Redding, Oakland and Sacramento — created challenges as each region saw different numbers of cases.

The demographics of veterans are also broad, as more younger men and more women serve in the armed forces. But young patients aren’t reasons to get careless.

“We’re at a point now where that level of vigilance is required regardless,” she said, noting the importance of precautions like wearing protective gowns and masks. “I may be taking care of somebody who is less likely to have complications, but if I’m not [taking the proper precautions], I could spread infection to somebody older and they may have complications. … That level of vigilance is required to break the cycle of transmission.”

Maniar said her experience with UC Davis Health, where she regularly treats patients who are hospitalized or being treated in outpatient facilities for infectious diseases, helped her better plan the VA’s COVID-19 response in the area.

“I’m not always rounding in the [UC Davis Medical Center], so I get snapshots as I rotate through,” she said. “Being a front-line health care worker helps me step into the shoes of people we’re working to protect.”

Still, it hasn’t been easy.

“I think early on it was to the point [where] I was losing sleep at night worrying about not just me individually, but worrying about the people I work with and the people who I’m trying to protect,” she said.

Maniar also said preparing for a short-term spike in cases is much simpler than working through a pandemic that shows no signs of disappearing.

While the initial surge in cases had calmed by this summer, the fall holds uncertain challenges, like managing an ongoing number of COVID-19 cases while distinguishing them from the flu, she said.

“We’re thinking about how to sustain this level of response for the long haul,” Maniar said. “It’s really hard to know where we’ll be in two weeks, much less two months.”

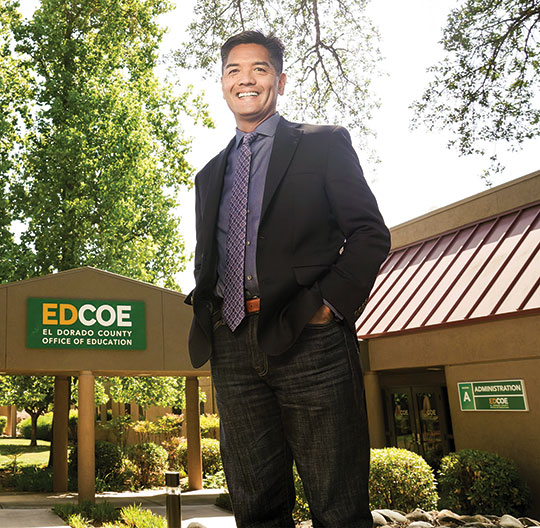

The County School Superintendent

Few things have underscored the importance of education like closing public schools.

Schools not only educate, they help children grow socially and emotionally, and support the local economy by caring for children while parents are at work, said Ed Manansala, Ed.D. ’11, El Dorado County superintendent of schools.

“The value of education has become that much more accentuated in the midst of the pandemic — how education is very much integrated in the fabric of many aspects of our communities,” he said.

And just as education is connected to things like the economy, allowing parents to focus on work, Manansala’s work is connected to what happens in other parts of the state and country.

As superintendent, he is helping coordinate between the 15 school districts in El Dorado County and public health officials, the state and members of the community. During the pandemic Manansala’s office has ramped up public outreach, releasing regular video updates to parents and media outlets.

Two days of typical meetings this summer had him talking with statewide, regional and local officials, and he said he is applying his knowledge regularly.

An added difficulty: the diversity of El Dorado County, which includes schools like Oak Ridge High School in El Dorado Hills, which has about 2,800 students and staff on campus during a regular year, and Indian Diggings School in Somerset, an elementary school with a total enrollment of 22.

Manansala said the pandemic has also given him the opportunity to strengthen partnerships with researchers like those at the five universities — including UC Davis — that oversee Policy Analysis for California Education, an independent organization that examines educational governance, effectiveness, finances and more.

“If I had to simplify — as educational leader I’m trying to be very collaborative in nature on multiple levels,” he said.

The situation has also given him many more family dinners with his two children, recent college graduates who are at home working or preparing for grad school.

The Olympic Hopeful

The pandemic has forced many to put their lives on hold, but it changed Solie Laughlin’s future.

Laughlin ’19, the most decorated swimmer in Aggie history, was a year into training for her second trip to the Olympic trials and had already qualified to compete for spots in two events when all future qualifying meets — and the Olympics themselves — dropped off her calendar.

“I’m kind of a retired athlete now,” she said. “I didn’t know my last meet was my last meet.”

She had been training in Davis with Pete Motekaitis ’83, associate head coach of the UC Davis swim and dive team, and knew she was physically ready to compete but wasn’t sure if she could mentally commit to another year of training.

Laughlin went home to Ventura after the cancellations. By early June, she was aching to train again and was trying to use running — not one of her favorite activities — to keep up her endurance. She also took occasional swims in the ocean.

“There are no lane lines so I have no idea where I’m going,” Laughlin said. “But I’m thankful to be able to get a 30- to 40-minute swim in sometimes.”

She spent free time picking blueberries and lost her voice at a Black Lives Matter protest.

July marked nearly five months out of a swimming pool, and she decided that was too long. She began researching graduate schools for a master’s degree in social work. She described herself as a driven person and said working toward something again felt good.

“Having this possibility in my future makes me feel like I have a path and a goal again and eases the pain of leaving behind something that is such a big part of me.”

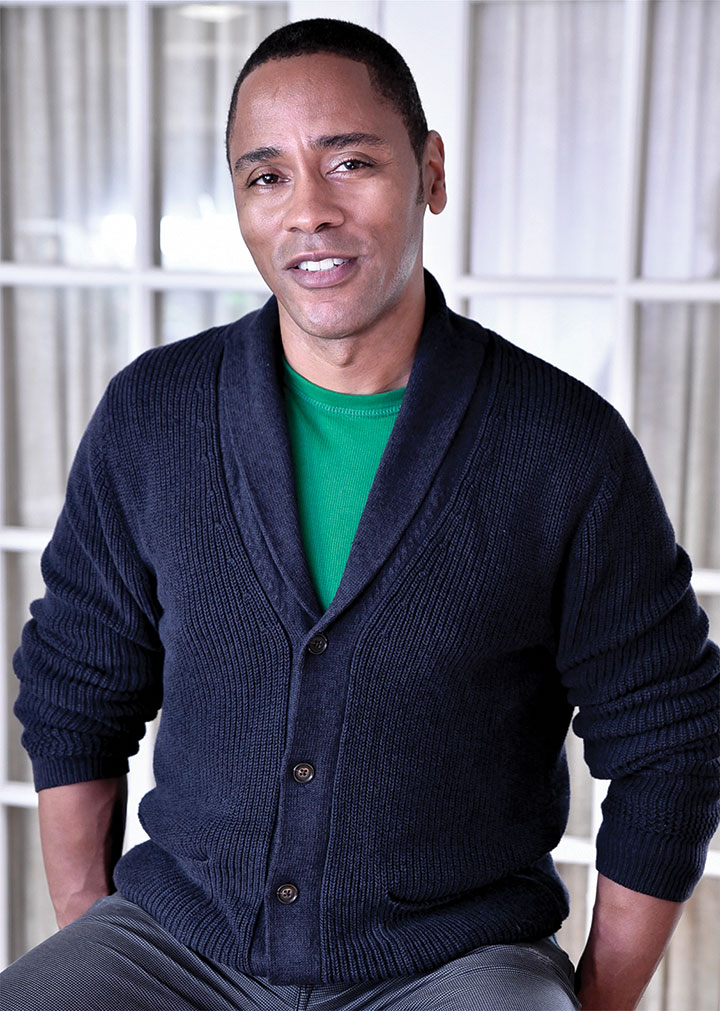

The Music Teacher

When New York City asked residents to stay home, Jesse Means ’91 figured he wasn’t going to be having any visitors anytime soon, so he might as well turn his living room into a studio.

Means, a Broadway actor turned elementary school music teacher, uses that studio to record weekly lessons that he said seek to not only educate but to uplift and encourage.

“My job is teaching, but my ultimate work is building up people and making sure their spirits are all right,” he said. “I became the modern-day Mr. Rogers, as some have referred to me.”

Mr. Means Music, his YouTube series, teaches rhythm, songs and vocabulary, but also includes assignments like asking students to write down something kind they did recently or a fond memory with a parent.

And because his lessons are public, he said he’s received fan mail from as far as the United Kingdom and Kenya.

“These little kids really need to have some normalcy,” he said. “They’re used to seeing specific faces every day, mine being one of them.”

While Means said he works almost straight through every weekend on new 10- to 20-minute episodes, he said seeing video reactions showing strengthening bonds between parent and child has made the extra work worthwhile.

One father, for example, regularly submitted videos of his daughter, sitting alone and responding to Means’ weekly questions. Partway through the school year, the videos changed.

“There was this very burly man who is now in the video with his daughter singing ‘the bell on the buoy goes ding ding!’ and touching his nose,” Means said. “You can see how much he loves his daughter. … That’s what keeps me going in those moments when I can barely keep my eyes open.”

The City Council Member

Being a parent of school-aged kids may be a universal struggle during the pandemic.

“Managing my own kids’ education — that’s a challenge,” said Angelique Ashby ’99. “That’s a challenge lots of moms are facing. I just happen to be mayor pro tem of the city of Sacramento.”

With her husband working long days managing the emergency room of Sutter Medical Center, Sacramento, Ashby said she’s spent much of the pandemic “Googling the answers to math questions I haven’t done in 15 years.” Of their three kids, two are still in school.

Ashby’s experience with remote education included assignments from her daughter’s first-grade teacher to watch YouTube videos of children’s books being read, a concept she thought could be localized.

“I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if these stories were read by the local police chief or the chancellor of UC Davis?’ ” she said.

Sacramento Police Chief Daniel Hahn and Chancellor Gary S. May eventually did lend their voices to what became Story Time Sacramento, a video series on Ashby’s website featuring Sacramento first-responders, athletes, health care workers and more reading their favorite children’s books.

“Everybody says we’re all in it together — and we are — but sometimes it doesn’t feel like it when you’re at home and feeling overwhelmed,” Ashby said. “Sometimes it feels nice to click on a website and hear a story from somebody in your community that your kids can enjoy, too.”

She’s sought to connect members of the North Natomas community she has represented since 2010 in many ways. Recent initiatives from her office have included a book club for teens led by Sacramento Republic FC player Sam Werner, subsidized Wi-Fi for those studying at home without internet access, grocery deliveries for seniors, and outreach to share mental health resources with teens after two separate Natomas suicides in April.

“It’s really our goal to just try to connect people and make sure no one feels alone as we go through COVID-19.”

The Journalist

Journalist Ignacio Torres ’10 began one of the biggest news stories of his life unable to leave his room.

“During the first two weeks of the original shutdown in New York City I actually came down with no smell, no taste and a small fever,” he said, recalling being told loss of taste and smell weren’t considered symptoms of COVID-19 at the time. “I couldn’t get a test. I ended up testing positive for antibodies [two weeks later], so I knew I probably was exposed to it.”

He stayed in his room for two weeks to avoid exposing his roommate and now does much of his reporting from home, coaching interview subjects to film themselves on their phones or take other video of their surroundings.

Covering the pandemic has required several shifts in perspective for New York-based Torres, who works as a producer for ABC’s Nightline, a late-night, in-depth news program.

The changing nature of the virus’ spread has meant journalists are learning new information at the same time as other members of the public, he said.

“Everything is so new it’s hard to get information prior to everyone else,” Torres said. “The briefings [from New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo] — we were sitting there watching them along with the rest of the public.”

And that has meant context is more important than ever, like the way COVID-19 disproportionately hurts disadvantaged communities. Torres saw it firsthand on a May reporting trip to Mexico, where he filmed makeshift graves and a 30-year-old doctor wondering if he might be next.

“I’ve seen how bad it can get, and trust me, it’s scary,” he said.

And amid the rising uncertainty of COVID-19, he said he doesn’t worry about distrust being directed at the media — he worries about people no longer believing scientists.

“The facts are the foundation of the human story I’m about to tell you,” he said. “The foundation of it all is the science. What I’m doing is just putting a face to it.”