When Ryan Fitch moved into his dormitory at UC Davis last fall, he had to leave his drum set at home in Santa Barbara.

“We figured that was a little too much for the dorms,” laughed Melissa Fitch, Ryan’s mom, as family members unloaded a refrigerator, boxes of clothing, and family photos to display in his new room.

Luckily, he was able to bring his guitar. Ryan is a musician and amateur photographer who aspires to a career as a band manager. He’s 19 and gregarious, with an infectious grin. He also has Down syndrome, a genetic condition that can cause developmental delays, intellectual disabilities and physical challenges.

Ryan is part of the inaugural group of Redwood SEED (Supported Education to Elevate Diversity) Scholars, a first-in-California, four-year residential program on a college campus for students with intellectual disabilities. Instead of bachelor’s degrees, the students will work toward a practical credential while preparing for employment.

Many of the nine scholars have Down syndrome or are somewhere on the autism spectrum. All have an intellectual disability that makes traditional college nearly impossible. Most had spent little time away from home prior to this school year.

“I wasn’t nervous at all,” said Ryan, who took the major life change in stride. “I already have friends here,” he explained.

He makes friends easily. His sister Jordan, who helped him move in, said he’s always asking people to join his band.

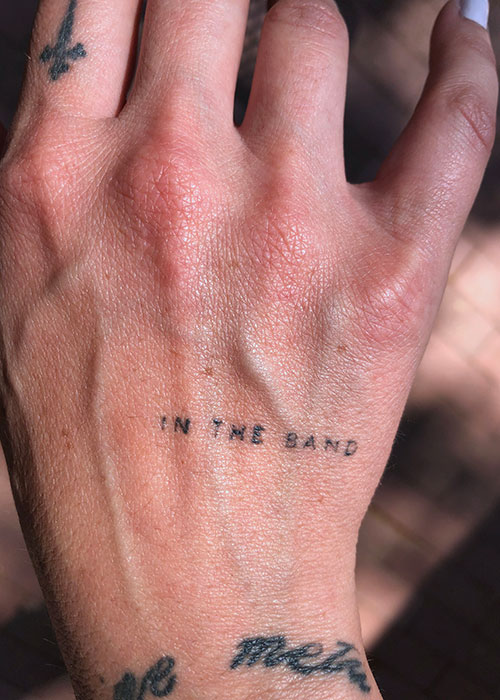

“It’s basically like, you come across him in life and you’re in the band. It’s not about the music — it’s a metaphor.”

In the Fitch family, if you’re “in the band,” you belong.

A vision of inclusion

Belonging is at the core of the Redwood SEED Scholars program. It’s grounded in the principles of diversity, equity and inclusion and the promise that students with intellectual disabilities deserve to be on campus. Post-secondary options are extremely limited for these students, with just a handful of four-year residential programs around the country — and no others in California.

The new program was created by the UC Davis MIND Institute, which specializes in the research and treatment of neurodevelopmental disabilities, and the UC Davis Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. But the vision comes from Beth Foraker, a high-energy instructor in the School of Education who is now co-director of the program, alongside MIND Institute Director Leonard Abbeduto.

Foraker’s 22-year-old son Patrick has Down syndrome and attends a similar program at a university in Virginia. She’s been working for years to bring an inclusive program to UC Davis. This is her passion.

“Just 3% of adults with intellectual disabilities make a living wage, which means 97% of adults with intellectual disabilities in our state are isolated socially and in poverty. That shouldn’t be tolerated,” she emphasized. “We should all be in the streets losing our minds about it, and we aren’t.”

Together, she, Abbeduto and Vice Chancellor for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Renetta Tull successfully applied for a $2.1 million U.S. Department of Education grant to create Redwood SEED Scholars and fund it for five years.

“We know that when you add inclusive post-secondary programs like Redwood SEED, that number moves from 3% to 65% to 80%, so it’s just astronomically different. It’s a total trajectory change,” Foraker explained.

Recently, the California Department of Rehabilitation agreed to pay the tuition for students in the program this year, a major boost for creating equitable opportunities.

“The UC Davis version of DEI [diversity, equity and inclusion] is focused on inclusion of all, and when we think about equity and equitable education and experience, we really want everybody to have that,” Tull said. “We feel strongly about this premise. It’s not just something we’re saying in our heads; it’s also something we believe in our hearts.”

Redwood SEED was designed using the model standards from Think College, the national coordinating center for post-secondary programs for students with intellectual disabilities. Foraker pointed out that inclusion is symbiotic; the benefits are not limited to the scholars.

“There’s something really important about elite institutions having these students on campus, because students who are here to get their degrees can get into an academic grind. But when you’re in a community with someone who has an intellectual disability that all changes because they [are people who] tend to live in the moment and prioritize other things,” she explained. “That influence matters. It’s a 100% value-add that really transforms the campus.”

The team hopes that transformation isn’t limited to UC Davis. The goal is to create a framework that other UCs and public universities can adopt.

For his part, Abbeduto said he is optimistic about that prospect. “I see a very bright future and an expansion of post-secondary options, largely because of the level of support and excitement for the program that we’ve encountered from everyone at UC Davis,” he said. “I hope that other UC campuses and other state colleges and universities will be as supportive.”

A path to meaningful employment

Sophie Howarth knew the career she wanted to pursue before she enrolled in Redwood SEED. “I want to do public speaking,” said the 23-year-old from Oakland. Howarth is confident and friendly. She has had experience with public speaking, too, as a global ambassador for the Special Olympics. She gave a speech to 500 people at the 2019 Torch Run Fundraiser.

She attended community college previously and loves to sing and dance so much that she brought a karaoke machine with her to school. Her favorite song is Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.”

A typical week for Howarth and the other scholars includes six foundational courses that are designed just for the program: literacy and writing, math and budgeting, sexual health, self-regulation, civics, and communication and technology. Some are taught by regular UC Davis instructors who also teach traditional courses. Other instructors — who include Sacramento County Office of Education specialists, a postdoctoral fellow at UC Davis health, an attorney with the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing, and a former elementary school teacher — are on campus just for the Redwood SEED courses.

Students are also taking their first UC Davis course — Nutrition 10 — winter quarter, with support from a teaching assistant. Spring quarter, the scholars will start taking traditional courses of their choice.

Howarth was worried about math. “I’m very nervous, because math is not my best friend,” she said back in September. Now? Math is one of her favorite classes, along with literacy.

Regarding the residence halls, “I love living in the dorms. It makes me happy,” Howarth said. “I like being with friends and doing fun things like going to Target and arranging birthday parties.”

Independence and inclusion are key, said Howarth’s mom, Maeryta Medrano. “To really have the whole student body embrace this idea of integration and inclusion, it’s remarkable. Having it wrapped under the MIND Institute at UC Davis and the concentration of that focus and interest of students that are coming here to study that, it really makes it a unique situation,” she said.

In addition to classes, the scholars will have internships. Organizations and businesses both on and off-campus, including at the State Capitol, have agreed to host scholars. The goal is a path to a living wage.

“We’ve created ladders of opportunity,” Foraker explained. “Let’s say they’re interested in animals; they might work on campus at the sheep, cow or goat barn or the Equestrian Center, then if they enjoy it, they could work at a horse stable in the city of Davis. They’re gradually learning how to take transportation, plan [their] meals, have a longer day, so that by the end of the four years they should be working three or four days a week, full-time.”

Sharing success

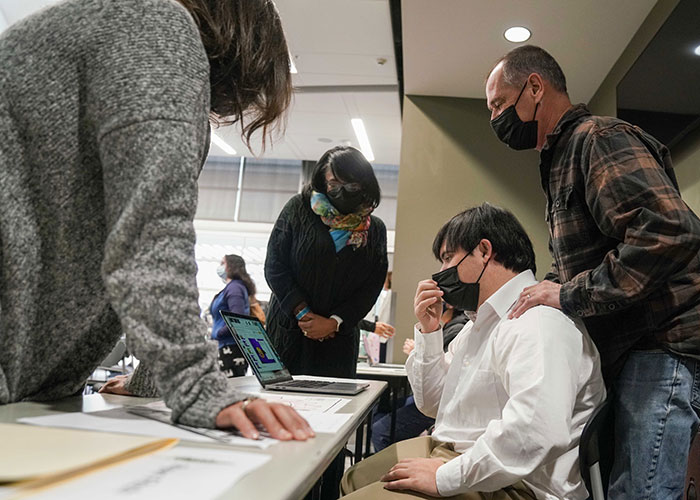

On a foggy Saturday near the end of fall quarter, the scholars and their family members gathered with their instructors at the International Student Center on campus. The students had prepared essays, presentations and work to share. Some were a little nervous as several dozen people filled large round tables in the multipurpose room.

“I actually feel proud,” said Olivia Adams-Falconer, a 23-year-old from Diamond Bar who has Down syndrome. She’d visited UC Davis several times when her brother was an Aggie about 10 years ago and had told her mom she wanted to attend college here.

“I felt like it was meant to be. I could not be more happy to be here,” she said. “For me, it felt like a home.”

Adams-Falconer said her favorite classes are civics and math. “I would love to have a job someday and an internship would be really cool.” She likes photographing landscapes and even has her own Etsy business selling photos, T-shirts and notecards.

“People with disabilities should be able to have the opportunity to take classes on a college campus,” Adams-Falconer said. “With us being the first program here, I feel like we are making history and I really like that.”

She added that it’s been fun to live in the dorms with a roommate. “She feels like a sister to me. We get along well, we do everything together, and we’re always being silly.”

Adams-Falconer’s roommate, 22-year-old Karis Chun, also has an intellectual disability and said the social aspect of a residential program has been an unexpected joy. “Back home, I was never really that social,” she explained. “Here, I’m around other people who are like me, so being around them, it’s like I have less pressure.”

Twenty-two-year-old Kai Gardizi echoed the focus on social connections and relationships with his roommates. “I can tell them what I’ve been going through, I can tell them what’s been going on in my life and they will understand.”

Gardizi has Lujan syndrome, a condition that usually includes intellectual disability and poor muscle tone. He said he hopes to study history, photography or music.

“I feel like I can actually make an impact on other people who are basically like me. I’m hoping to make this world a better place for people with disabilities and people without disabilities. It’s about coming together.”

The experience is also about life skills and independence. Some students mentioned laundry and making their beds daily as a new challenge.

“The toughest thing is I’ve been sleeping in a lot and I’ve actually missed a couple of classes,” Ryan Fitch said. “Getting up is really tough.”

He admitted that he was learning how to manage his time. “One night I was working on my homework in the middle of the night.”

“They’re drinking coffee, taking naps and doing late-night Target runs — like other college students,” said Jonathan Bystrynski, who teaches the self-regulation course. He’s a clinical psychology postdoctoral fellow in developmental behavioral pediatrics at the MIND Institute whose research focuses on the intersections of trauma, disability and justice.

“The students have shown such creativity but also bravery, taking the plunge in this big unknown of college — and in a program that’s very new. They’ve taught me new things about not only the content I teach, but also how I can be as an instructor. I feel indebted to the students for their work and for the future that they’re going to push for.”

A system of peer support

The Redwood SEED Scholars team has built a broad support network. That includes a group of about 40 peer mentors who are tending to the academic, social, residential, health and wellness needs of the students.

The mentors come from a variety of majors and from both the Sacramento and Davis campuses, including the UC Davis School of Medicine.

Elizabeth Twomey is an English major who’ll graduate this spring. She signed up to be a residential mentor after taking a seminar that Beth Foraker teaches about being an ally for individuals with intellectual disabilities.

“I want to go into education policy and improving education equity and things like that with my career,” Twomey said.

Once in the morning and once in the evening, Twomey or another mentor comes into each quad of students to check in. They may grab a meal together, take a walk or just chat about how things are going. There are also regular social outings, like bowling, sporting events and crafts.

Twomey said the experience has already affected her deeply.

“It’s really ignited a passion in me that I didn’t really know was there,” she said. “Diversity, equity and inclusion needs to include all types of people, not just focus specifically on race or gender or anything like that, but also intellectual disabilities, physical disabilities, all of those things.”

Tonya Piergies is a first-year developmental psychology doctoral student who’s working at the MIND Institute, studying social communication and self-regulation development among children at an increased likelihood for autism and ADHD. Piergies is a health and wellness mentor, meaning she meets with a different scholar each week for an activity and to chat about daily habits and how they can influence overall well-being. For example, she might go to the Dining Commons or the Activities and Recreation Center with a student.

“I’ve shared lovely moments with all the students!” she said, remembering one notable anecdote that took place over dinner a couple of months ago. Piergies said a scholar asked to sit at a table with other UC Davis students who weren’t affiliated with the program, and the other students instantly welcomed the student into their conversations.

“This interaction ended with the student being invited to a get-together that weekend. The ease at which acceptance and integration were achieved in this moment exemplified that, when given the opportunity, the students do belong and can thrive at a higher education institution,” she said.

Systems change

For Foraker, this is just one example of what drives her. The growth and integration aren’t limited to one program: They’re systemic.

“All of these mentors will go into their future jobs and change the systems there. We have a second-year medical student who is a mentor. Imagine her as a doctor! Even the head of Picnic Day is a mentor, so imagine that event now through the lens of disability-forward thinking.”

Foraker continued, “There’s a bus driver who’s a mentor and a volleyball coach who wants all their players to take my mentor seminar. It just starts transforming systems, and that’s how you become visible when you’re currently invisible.”

Self-regulation instructor Bystrynski agreed and pointed out that the program’s impact goes far beyond the direct benefits to the scholars themselves. “I believe the program’s real power may be in teaching our systems to dispel the practice of underestimating and marginalizing the disability community.”

Melissa Fitch, Ryan’s mom, said she knows exactly how that works. Growing up in Santa Barbara, Ryan went to a small neighborhood school, and because he was outgoing, everyone knew him.

“He brought something to that school, that community, that nobody else ever could,” she explained. “To have a kid with a disability be included and be just part of the community and just another kid on campus, he taught families and so many people about acceptance. Being included helps everybody.”

Like most parents who send their kids off to college, Ryan’s family misses him.

A few months before Ryan started the Redwood SEED Scholars program, his sister Jordan got a small tattoo on her right hand. It reads, “In the band.”

“It’s just for me. I don’t see ever wanting to take this tattoo off,” she said.

Ryan chats via FaceTime most days with his parents, and Melissa admited that she even misses hearing him playing the drums. But she’s glad he’s thriving.

“He’s happy, making friends, growing up and doing great!” she said.

You could say his “band” is getting a lot bigger.

_______________________________________________________________

Applications for the next group of 12 Redwood SEED Scholars are being accepted now. Learn more about the admissions process.