From the U.S. president to the UC president, when leaders have wanted help with a sticky situation — reviewing voting irregularities, civil rights issues or a police action, leading a commission or task force, or mediating a controversy — they often have called on Cruz Reynoso.

The UC Davis law professor emeritus and former small-town lawyer who became the first Latino appointed to the California Supreme Court always offered a warning: “Just be sure you know, I am known for having an opinion, and I’m not afraid to state it,” he said, a serious face giving way to a quick smile. “And they’d tell me they want me to do it anyway.”

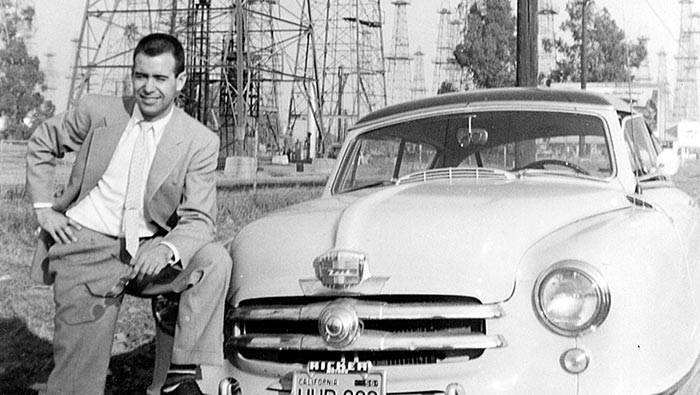

Now retired from teaching and public life, Reynoso is looking through papers, books and old photographs as he works on his memoirs in his offices at his Davis home and a local law firm. A poster-size card, handwritten and signed by his adult children, hangs inside the front door of his home reminding their father to write his memoirs. “My children,” he gestured toward the poster board and smiled. “Still telling me what to do.”

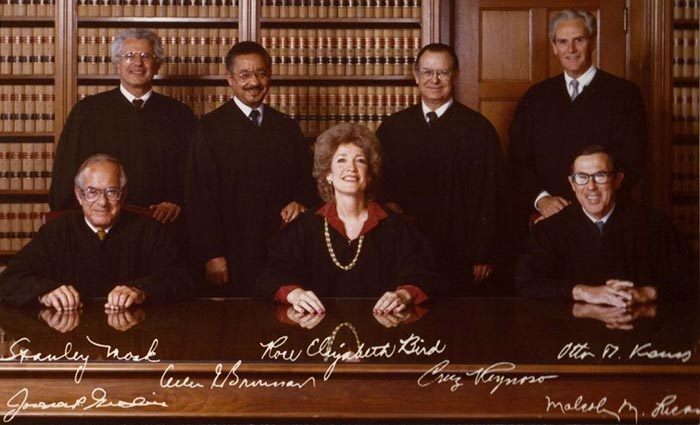

The public might know him best for his ouster from the state Supreme Court in a venomous campaign that also unseated two other “Rose Bird Court” justices in 1986. But in his closer circles, he is better known for his many accomplishments and service outside his five years on the high court bench.

Earning the right to be called ‘honorable’

His lack of popularity in some circles is the very thing that has brought adulation in others. He has served under four U.S. presidents and three California governors. When introduced to public audiences, he is the Honorable Cruz Reynoso. The “honorable” refers to his time in the judiciary. But he is honorable in countless other ways to his many admirers: Migrant farmers who have sought his counsel and paid him only with a box of lettuce; students who have listened to his lectures and made good-natured fun of him for his Socratic technique of saying “query” before he poses a question.

He was a caregiver to his late wife of 50 years and then again for his second wife. Until recently, he rose before dawn to attend to his wife, Elaine Rowen Reynoso, who was critically injured in a 2010 car accident. She passed away in late 2017.

When asked, he said he sees himself as professor, lawyer, farmer, a fussy grandpa known for taking many of his 17 grandchildren on trips — even cross-country by rail; a father like any who worries for his adult children, who range in profession from artist, to educator, to lawyer. Photos of his immediate and extended family fill his home. In the last year he welcomed his first great-grandchild.

Many biographies list him simply as “civil rights activist.” He would be the first to say he is just “folk,” a term he uses when addressing others in audiences large and small.

At 87, he is still active. For most of his teaching life, he went to his office at UC Davis, often arriving by 7:30 a.m. in suit and tie, toting a large briefcase. He has taught “Remedies” on occasion, one of his favorite courses to teach, and he speaks to nearly everyone who seeks his conversation. Now he dresses more casually and spends much of each morning working on his autobiography.

A life of righting wrongs

“I became a lawyer because I saw so many injustices,” Reynoso says.

He still does.

He lamented that too many people still don’t have health insurance. He said he wishes more law students went into public service but understands the financial limitations. He said he wants to see more done for civil rights. Most of all, he lamented the poverty he sees everywhere. “I don’t know what the solution is, but it has to be a multi-pronged approach,” he explained. “There are so many ways people can become homeless.”

Born one of 11 children in the Orange County town of Brea to a farmworker family, he witnessed injustices at an early age, beginning with his enrollment in a segregated grade school for children of Mexican descent. “They told us we had to attend that school to learn English. But my brothers and I already spoke English. That didn’t make sense.”

He saw other injustices. Failure to deliver mail to the Latino barrio where he lived. Segregation at a high school dance. He fought them all.

Life as ‘Bruce Reynolds’

After graduating from Pomona College, he joined the Army, serving in the Counterintelligence Corps. His fellow soldiers were confused by his name, he recalled. “They called me Bruce often, because they had never heard the name Cruz. Reynoso was strange to them too, so they assumed my name was ‘Reynolds.’ So, when someone called for Bruce Reynolds, I answered.”

After graduating law school at UC Berkeley, he studied constitutional law at the National University in Mexico City. He had the credentials for many legal pursuits, but he aimed to be a small-town lawyer. After returning to California, he went into private practice in the Imperial County community of El Centro, near the Mexican border.

He worked initially for a small firm and then hung out a shingle and ran a practice where he did everything — workers’ compensation cases, civil suits of various kinds and divorces — while his wife, Jeannene, ran the front office.

Getting political

In 1964, he was recruited by the local Democratic Party to be the county’s first Latino candidate for the California Assembly. He lost.

He decided he didn’t like running for office. And at that time, of course, he didn’t foresee the kind of publicity he and his colleagues would be subject to in the campaign to unseat him as associate justice in the 1980s.

In 1993, Reynoso was appointed by Congress as vice chairman of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, and later reappointed by President Clinton. During his 11 years of service, the commission looked at a range of issues: from civil unrest following a Ventura County jury’s acquittal of four Los Angeles police officers accused of beating motorist Rodney King to voting irregularities in Florida in the 2000 presidential race between Al Gore and George W. Bush. Reynoso criticized that election, saying the “greatest sin” was that people were not allowed to vote.

From rural poor to the California Supreme Court

In the late 1960s, Reynoso was the first Latino to direct California Rural Legal Assistance Inc., which assists migrant laborers and the rural poor. Then-Gov. Ronald Reagan tried to cut CRLA’s funding, but the agency resisted the challenge.

During those years, Reynoso remembered, he thought he might like to be a judge someday, but figured no one would ever appoint “a trouble-making lawyer” like himself. “Jerry Brown had other ideas,” he quipped.

Brown, during his first gubernatorial term, appointed Reynoso to the Third District Court of Appeal in 1976 and elevated him to the highest court in California in 1981. Reynoso said it was a good job. “I could make decisions based on what is right and lawful, and not worry about what people think.”

That was how he viewed it, anyway. But then came the infamous “Bird Court” ouster. Up for confirmation a year after his appointment, Reynoso survived a first attempt to unseat him and other justices. That recall effort, Reynoso said, was led by George Deukmejian, the state attorney general at the time who had opposed his initial appointment and was a major advocate of capital punishment. (Deukmejian later was elected governor in 1982.) A second challenge in 1986 — aimed at Reynoso, Chief Justice Rose Bird and Associate Justice Joseph Grodin — was successful. The campaign against them, accusing the three of being soft on crime and failing to enforce the death penalty, was well-funded.

Reynoso actually had voted to uphold California’s death penalty, but the firestorm of criticism buried his judicial record, which included extending environmental protections and individual liberties and protecting civil rights. As justices, they chose to stay out of the political fray, taking out no ads and engaging in no political messaging. The ouster gave then-Gov. Deukmejian the opportunity to appoint three conservative judges to the state’s high court.

Reynoso said he still sees such politicizing of the judiciary as a major flaw in the governmental system of checks and balances. “Judges should not be thinking about the next election when they are making court decisions. That’s not justice.”

Life after the Supreme Court

After the Supreme Court, Reynoso returned to private practice but was called to academia. He joined the UCLA School of Law faculty, where he taught for a decade.

Susan Prager was dean at UCLA at that time. “His decade at UCLA was truly extraordinary for all who were taught by him or came to know him because he is such a unique combination of wisdom, determination, purpose, passion, humility and impact,” said Prager.

While at UCLA, Reynoso advised the Chicano-Latino Law Review, and served on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and a special dean’s committee.

The UC Davis years

Kevin Johnson, dean of the UC Davis School of Law, as associate dean at the time, worked with then-Dean Rex Perschbacher to bring Reynoso to UC Davis in 2001. The shorter commute and the offer of an endowed chair were major enticements in luring him to King Hall.

Dedicated to freedom and equality at UC Davis, he would be called upon in 2011 to provide another service to the University of California. That was when then-President Mark Yudof asked him to head a task force to investigate the pepper spraying of students by UC Davis police after a days-long “Occupy” movement protest on the Quad.

The panel, which became known as the Reynoso Task Force, concluded in releasing its report in April 2012 that officers’ use of pepper spray was unjustified.

The university responded to this report and other studies with various reforms in place today.

Reynoso’s effect on students throughout his academic career is immeasurable.

“He is a legal giant and a social justice icon,” exclaimed Adrian Lopez ’00, J.D. ’03, a former law student of Reynoso’s.

“As an immigrant, English language learner and former continuation school student I was blessed to have achieved a law degree,” said Lopez, who is now director of state government affairs on campus. “Cruz taught me that I had a moral imperative to give back to those that weren’t as fortunate in life’s journey.”

Johnson spoke about Reynoso’s humility.

“I have never met somebody so humble, decent, caring and down-to-earth as Cruz Reynoso,” said Johnson. “He treats all people — students, faculty, opponents of his views and others — with respect and humanity. I never have known him to say anything mean to anybody. I truly cannot think of a more decent person.”

READ MORE: UC Davis School of Law’s Counselor magazine