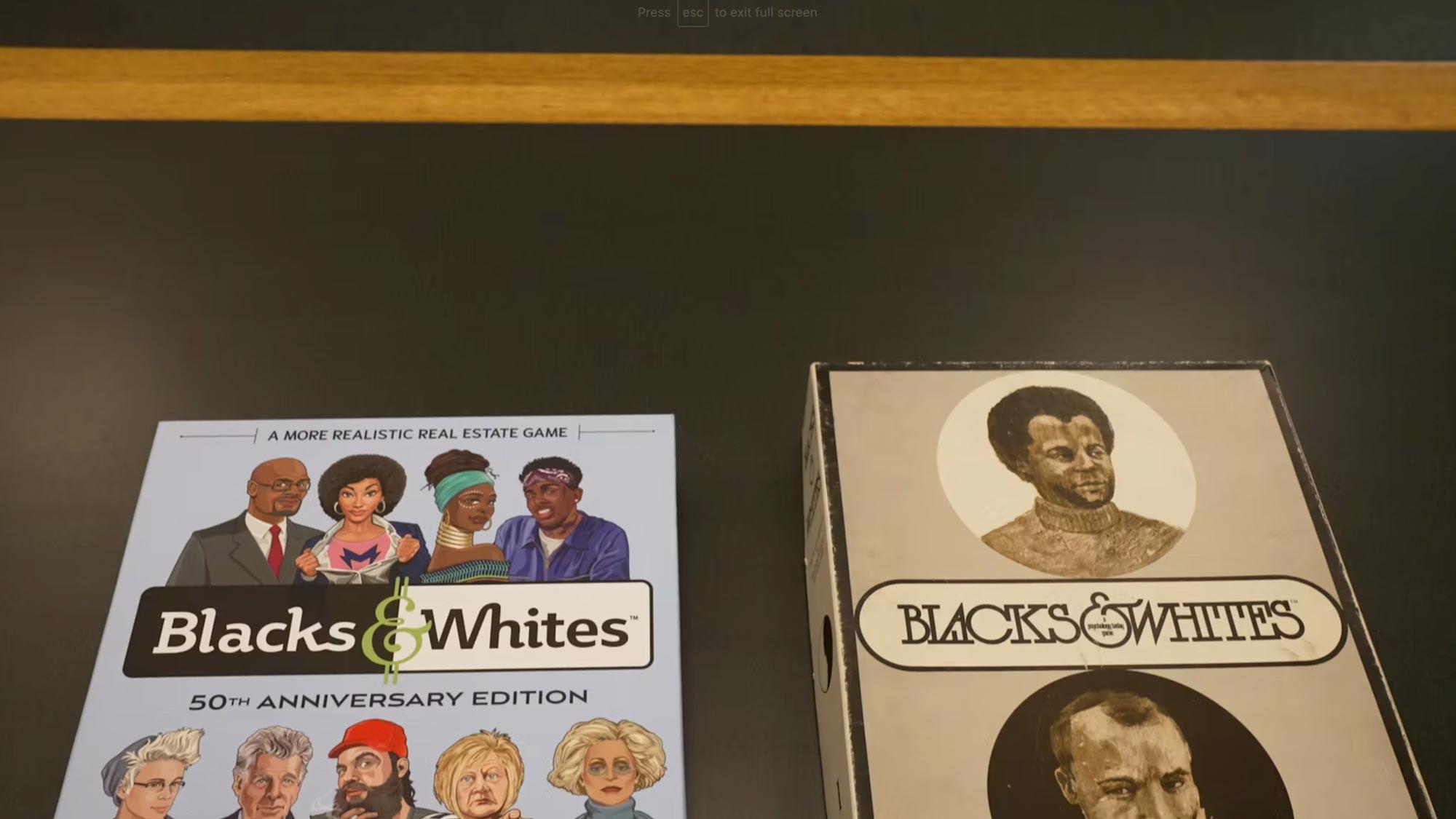

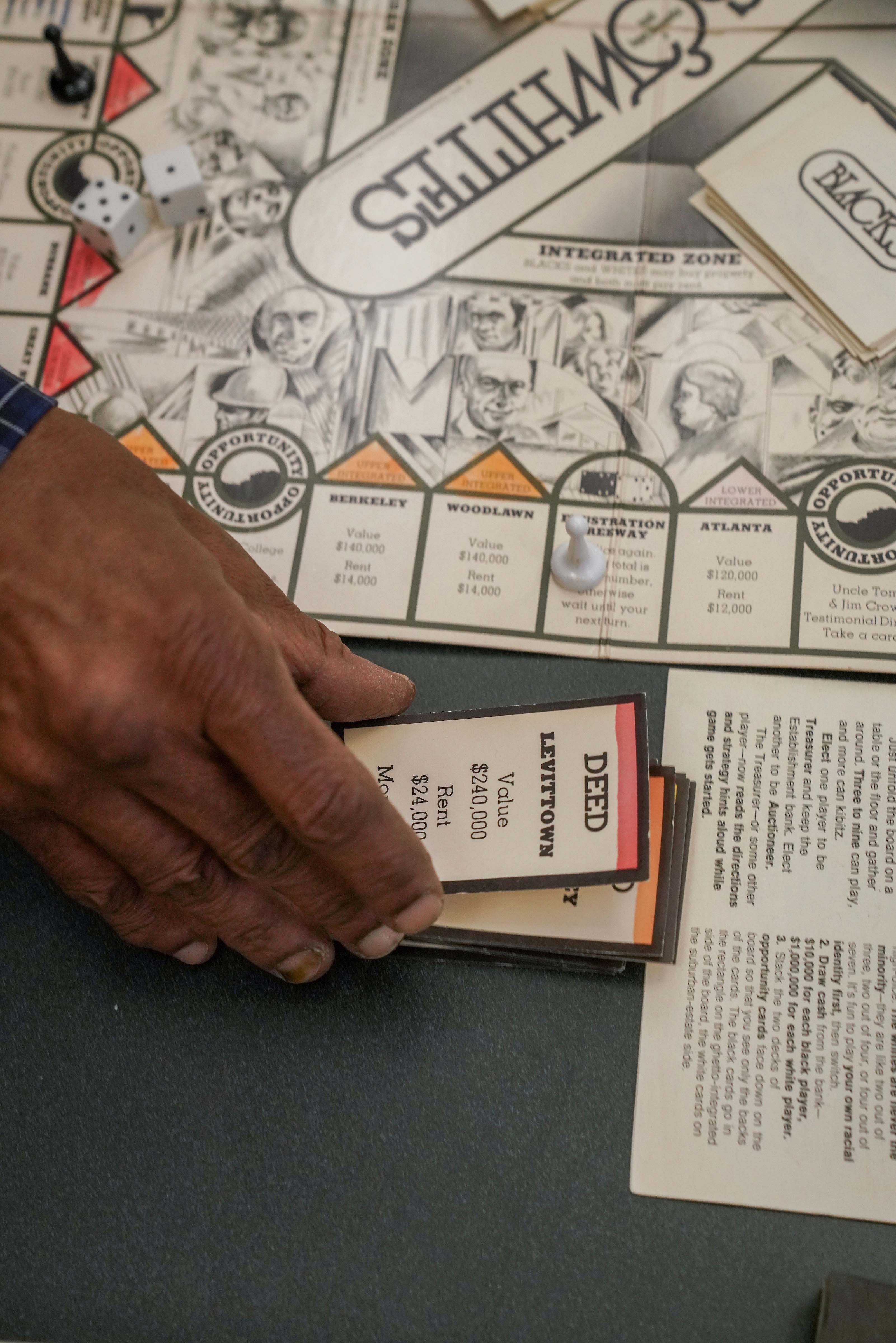

New York comedy duo and best friends Nehemiah Markos and Jed Feiman first discovered the UC Davis-created Blacks & Whites game in 2016 when they read an article about it in Slate. The game was created by the late UC Davis Professor Robert Sommer and his friend Judy Tart in the 1960s. Published by Psychology Today in 1970, it was conceived as a racially conscious version of Monopoly.

Feiman and Markos found the old board game online and purchased it.

And the rest is history — still in the making.

Blacks & Whites origins

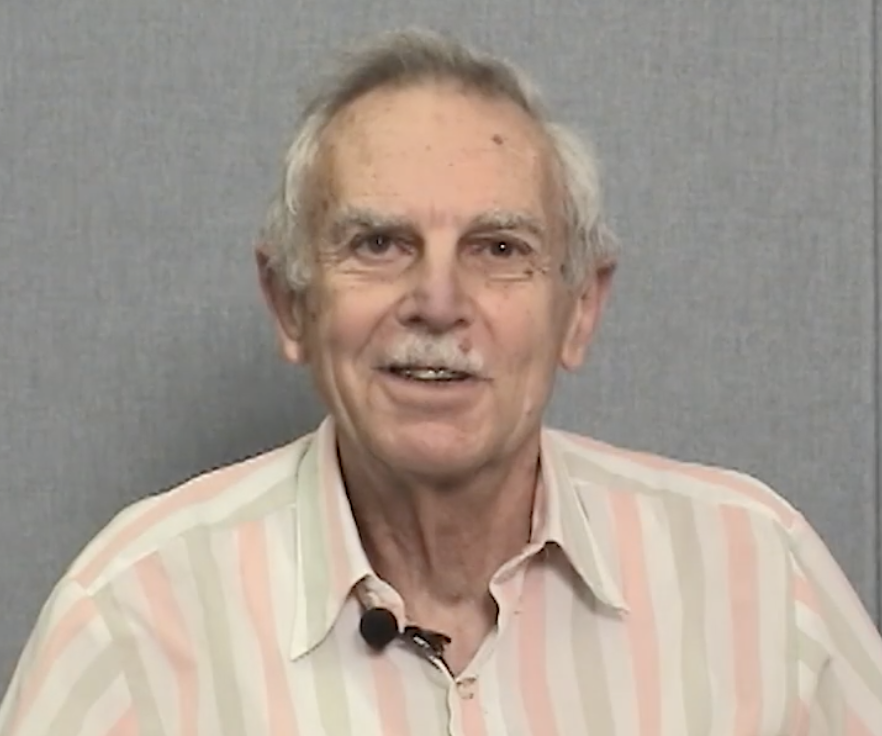

ROBERT SOMMER

UC Davis professor of environmental psychology, 1963-2003

Sommer, an environmental psychologist, had always said that he wanted to leave the world a better place. During his 40-plus-year tenure, he researched and made recommendations for the layout of farmers markets, where human interaction was tantamount to their success — a type of market layout still prevalent today. He developed the current Davis bicycle path system.

And when watching his three children play the seemingly innocent game of Monopoly, he became enraged, even though he’d loved playing the game himself growing up. He didn’t want them indoctrinated into becoming “monopolists,” as the game rules dictated.

So began Sommer’s quest to create a game that might help illustrate racism in society.

“As an observant adult living in socially conscious times, when every act had political implications, I viewed [Monopoly] differently,” Sommer, a white man, wrote in 2008 — four decades after creating the board game Blacks & Whites, his own version of a Monopoly-style game.

“The content of the game seemed unrealistic, and worse, the rules of the game immoral,” he wrote, lamenting: “The game explicitly encouraged illegal behavior.”

Sommer, who died last year, in creating this “teaching game,” collaborated with Tart, the wife of UC Davis psychology faculty colleague Charles Tart. Blacks & Whites was manufactured, published and sold to consumers by Psychology Today in 1970, with an article, rules and special tear-out version of the game available in the March 1970 edition of the magazine.

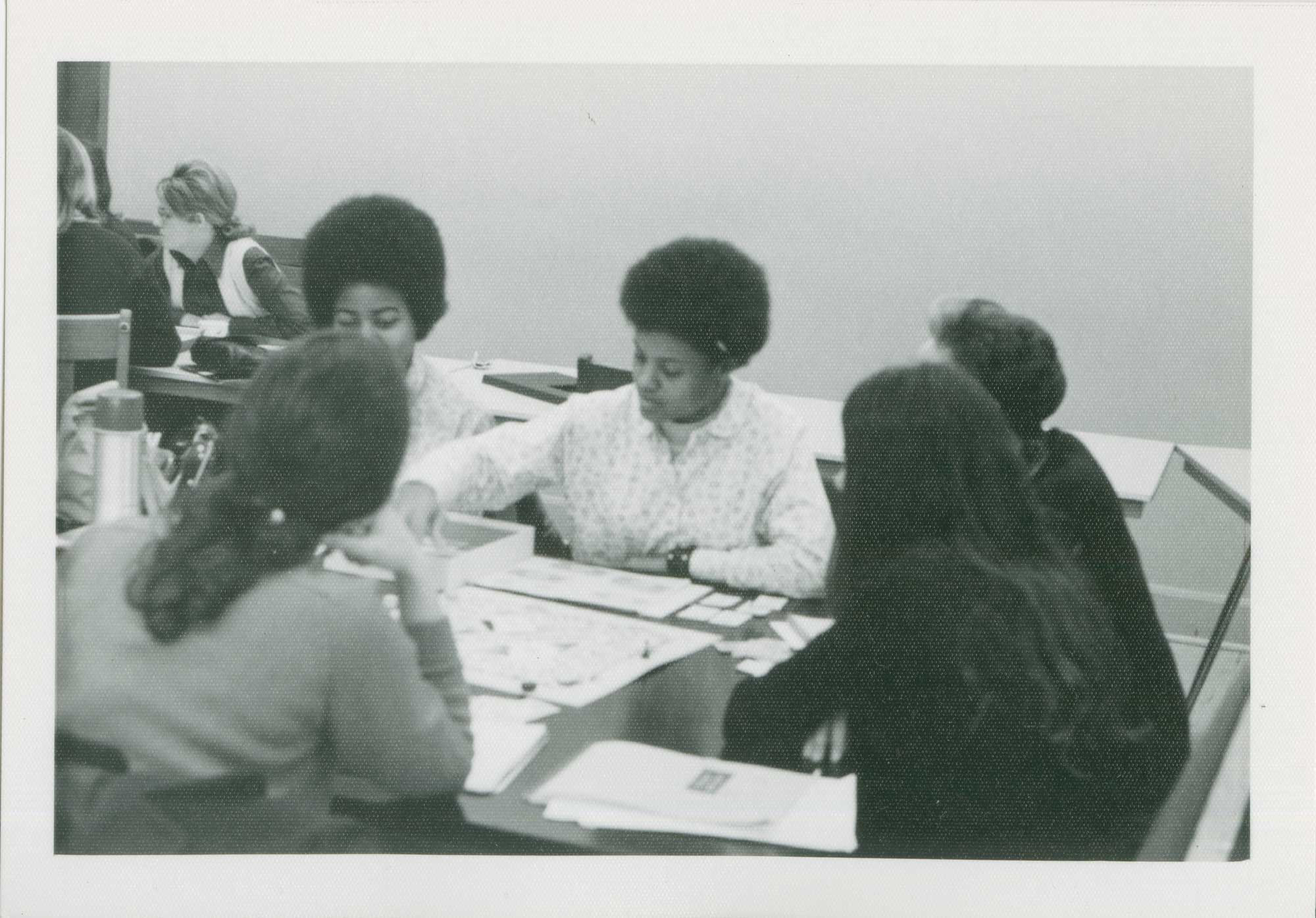

The magazine at that time also sold the board game by mail order, complete with play money, dice, play pieces and the cards for $5.95. Sommer said in a letter to a colleague, filed in the UC Davis Library archives, that Psychology Today sold thousands of copies.

2020 events inspire 50th-anniversary edition

Jump ahead 50 years to 2020 when the millennial writer-comedians, Markos, who is Black, and Feiman, who is white, were playing with an old edition of Sommer’s game.

“We played it with our friends,” Feiman remembered, “and we kept thinking, you know, someday we could remake this and update it.”

The New Yorkers found themselves, like a lot of people, with less work and more time on their hands during the COVID-19 shutdown. George Floyd was killed by police. Other acts of police violence involving people of color continued. There was civil unrest.

The time was right for a 50th-anniversary edition.

They tracked down Sommer at his Davis home and sought his permission. They got an enthusiastic endorsement, part of which is scribed in the current game’s instructions. Sommer died before the anniversary game was produced.

There is still something about privilege you can learn from playing this game. Way too many people are oblivious to the facts. — Nehemiah Markos

The two men, who’ve performed in a variety of live comedy shows and videos, and written regularly for The New Yorker column “Daily Shouts,” said in an interview they felt the older game had real relevance, even today. But they decided updates on property names and location, social realities and current events would make it more fun and socially conscious at the same time.

They researched current neighborhoods that should be in the appropriate designated neighborhoods, whether that be in their newly named “1%” area or the lower-priced, ungentrified, integrated or suburbia zones.

They updated the social realities of the day, too. There were 1970s references in the first game that aren’t easily understood today, so they came up with their own. They added characters, as well, that each player could “play” in the game — a Watts native named Zemari; her friend Rico, and, of course, a Karen character, to name a few. The game comes with stickers of the characters’ faces that can be placed on each piece, and it has a modern look and feel that comes to life with illustrations by Ericka Kitrel.

Markos and Feiman think Sommer’s version and their newer game each can teach people about racism and privilege. They admit they would like to address issues with other ethnicities, but for now are now sticking to the theme of the original game.

“There is still something about privilege you can learn from playing this game,” Markos said. “Way too many people are oblivious to the facts.”

UC Davis Library acquires original game

Sommer’s widow, Barbara Sommer, who had been a lecturer in psychology at UC Davis, had given her husband’s papers to the UC Davis Library after his death last year. Then, after Wired broke the story in the fall of 2021 that Markos and Feiman were developing an updated 50th-anniversary edition, UC Davis Library archivists retrieved the game, too, and notes and letters related to its creation, from Barbara Sommer.

Tart, reached by email, remembered that ideas for the original game came up in discussions with the Sommers. “We spent some good time together pondering possible meaningful names for the stops along the way (in the game), and how the cards would be tilted to show the unfairness of our society and the prejudice against people of color,” she said in a recent interview. “We worked on the game, played with it and felt it had something to say — but it was Bob Sommer who had come up with the idea, who spent many hours on it and produced something that still is relevant today.”

Throughout his whole life, said Barbara Sommer, “he was always concerned about racism.”

“He was really glad that the discussions about his game were continuing.”

Kevin Miller, head of archives and special collections at the library, said he and his colleagues were excited to get the board game and the file box of research that went with it.

“Getting a copy of the original game and all of Professor Sommer’s notes and letters about its creation felt like Christmas morning,” he said. “Flipping through the memos, correspondence, reference articles, design mock-ups and photos was like reading a novel. The story of the game’s origins and transformation — in fits and starts — unfolds through this material, and should be fascinating for future researchers on gamification, social justice and a whole host of related issues.”

Sommer sought to make a realistic game

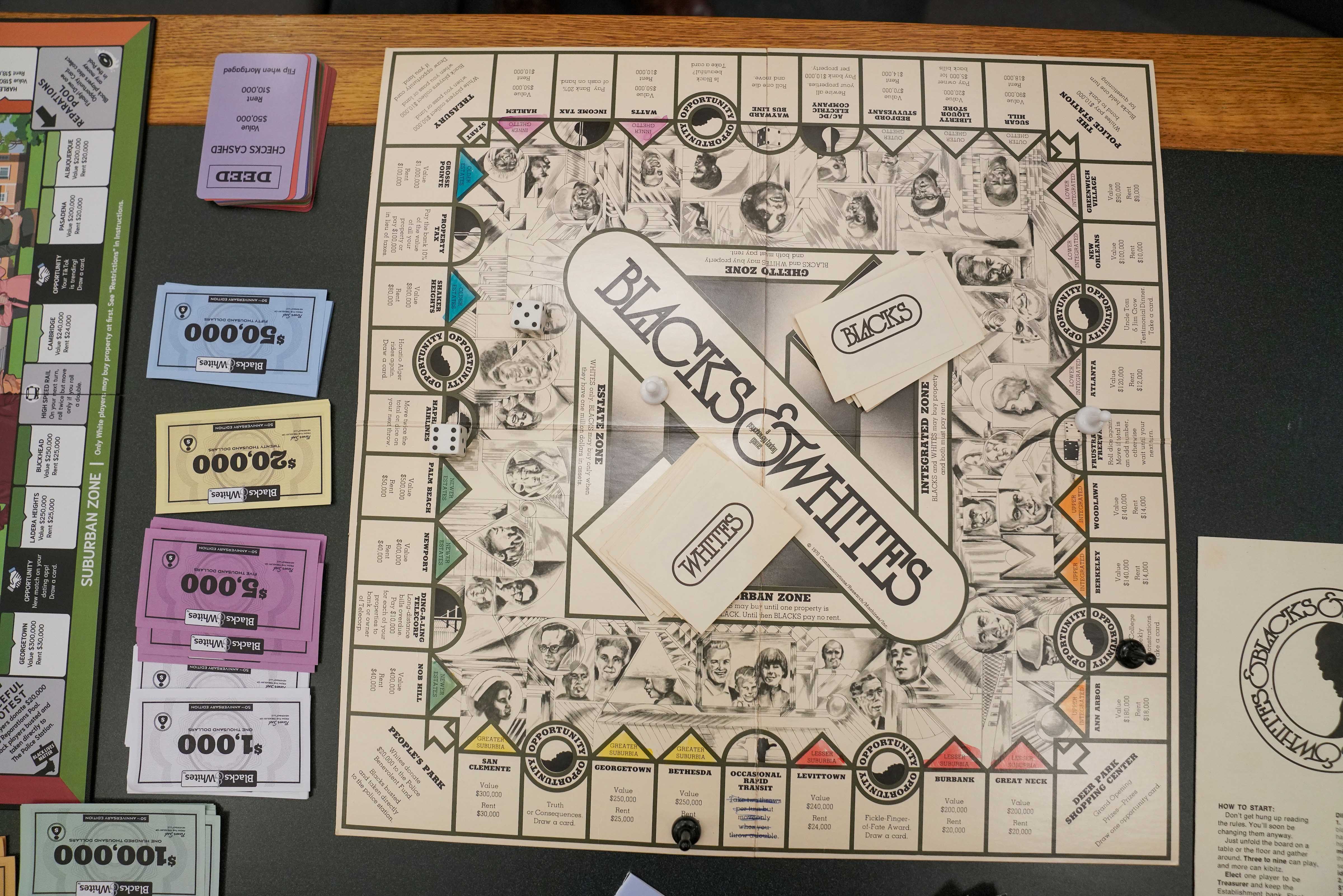

Sommer’s game had rules about buying property, just like the Parker Brothers Monopoly game did. In his version of mid-20th-century redlining realities, the game restricted people of color from buying in certain areas. A white player could buy property in any zone, but a Black player could buy only in what were called the “ghetto” and integrated zones, with few exceptions.

In the game, Black people had to pay high rent for any property and had little opportunity to elevate themselves economically. All property had buildings on it, something Sommer wrote he decided was more realistic in 1970, as opposed to the original Monopoly game.

The 2020 game has similar neighborhoods, but does away with the “ghetto“ term — instead having a “gentrified zone,” an “integrated zone” and a “1% zone.” The rules are similar, and like the Sommer version, players can change the rules whenever they wish.

Sommer obtained permission from the original Monopoly game’s developers, he said in his papers, “clearing all legal hurdles.” In fact, Parker Brothers rejected the idea of manufacturing the game itself, saying, according to an account in a 1979 article in the Saturday Review, “A game should be an escape, not a confrontation.”

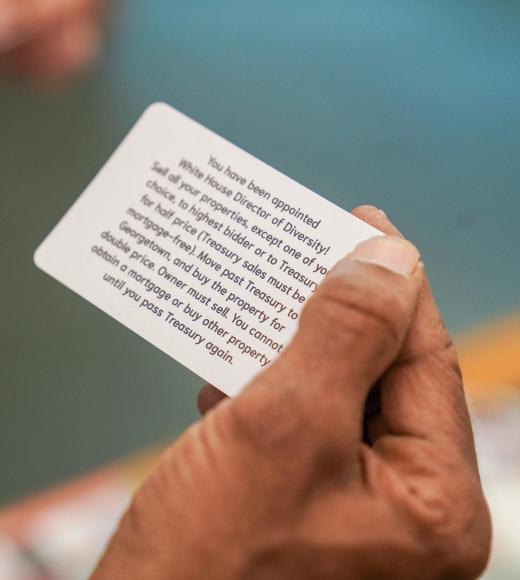

Sommer noted in his writings that he purposely made his take on the original game unfair for Black people. He explained that was so white people, playing the role of Black people in the game, could understand that the odds of succeeding financially were literally stacked against Black people. This was evidenced in the “Opportunity” cards (one stack for Black players, one for white players) that were “separate and unequal,” he said.

Each game reflects its time

Bruce Haynes, a UC Davis sociologist who has studied and observed changing Black culture and history through his teaching, books and other writings, noted that each of the games reflects the period in which it was created. While the 1970s version refers to political figures of the time and names certain neighborhoods in particular “zones,” the new game similarly reflects current times and neighborhoods.

The early version of the game depicts on the game’s box and board caricature drawings of Black people that Haynes said he found somewhat offensive, but added that they also reflect some of the artwork in humorist magazines at the time, such as MAD magazine. Sommer’s letters in the library archives reflect that he had objected to original drawings that Psychology Today used, also, but it’s unclear how this changed before production.

Haynes added that the new game updates neighborhoods accurately. Harlem, for instance, is in the gentrified zone, which is accurate now, but would not have been accurate in the ’70s, he said.

Additionally, references from the 1970s game were more political than the social media-type references and icons featured in the newer game.

While the older game carries references to Vice President Spiro Agnew (when he fictionally is elected president, the Black player must go back a few spaces) and Mayor Richard J. Daley of Chicago, the newer game reflects more pop culture and humor, observed Jorge Peña, UC Davis associate professor of communication who serves on the Games Studies Division of the National Communication Association.

An “Opportunity” card in the new game, for example, offers a scenario in which the player was seen in a photo with the late convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, causing a game penalty for that player.

Addressing racism

Both Haynes and Peña said they wondered how learning would be applied in each game.

Haynes said it is difficult to translate social outcomes to an individual level. “There’s a lot of randomness happening to individuals, in reality, that can’t be reflected in this setting. … It’s monolithic.”

Chris Coleman, a Washington, D.C., native who has lived in many gentrified neighborhoods himself, is studying some of the effects of redlining and racism in a longitudinal study while pursuing his doctorate degree in social psychology at UC Davis. In his research with Alison Ledgerwood, UC Davis professor of psychology, they have found that people acquiring knowledge of systemic racism, and understanding and even empathizing with it, changes fast through history. But it does not turn into action immediately.

So, Coleman said, the efforts of Sommer and those like him to undo the damage of games like Monopoly, or similar actions in society, might take generations.

“It’s a zero-sum game,” Coleman continued. “White people are motivated to protect their white identity (the self)." While people may accept that group-level privilege exists, he explained, they often discount the role of systemic privilege in their personal lives.

“People don’t act because they think that action would take away from their own resources — resources that they believed they earned due to hard work. Thus, the motivation to dispel inequalities is stunted by the combination of this desire to not lose their identity (as deserving of their benefits) and a desire to physically protect the benefits that they would lose as a result of systemic change.”

He observed that the game of Monopoly has a sinister quality. “It melts into the idea of fairness. … Everyone starts out with the same amount of money.” But, at the end of the game, its conclusion shows what really happens in society. “Nobody ends up that way.”

Can games reinforce stereotypes?

It’s not clear the games’ efforts toward engendering empathy always work.

Peña said he was concerned that the Blacks & Whites games from both 1970 and 2020 might reinforce stereotypes rather than teach about them. He has looked, in his own research, at people’s perspectives and feelings of empathy as people played video games — a more fast-paced version of game-playing than board games.

Games where players take on a role different than their own perspective can shed light on empathy and feelings toward other groups, he said. Scholars call it “perspective-taking,” and it refers to the cognitive and emotional capacity to consider the world from other viewpoints and understand and anticipate the behavior of others. Much of the research shows that allowing players to embody, for example, a Black student experiencing racial prejudice, decreases feelings of prejudice.

However, there can be what he called a “boomerang effect,” where the game player begins to identify with their character. This happened in two of his research studies — one in the United States, using mostly white college students as players, and another study using Spanish college students with different life experiences.

He said a good experiment with Blacks & Whites would be to have players play anonymously, similarly to how games can be played by video, so that they don’t know who is playing with them. That way, he said, players couldn’t change their remarks or reaction to meet expectations of their friends or acquaintances.

Ideas for the game continue

The creators of the new game said they’ve gotten mostly favorable feedback about the current game.

“Our haters want us to be post-racial,” Markos said. “They say, ‘Oh, we are beyond that.’ But clearly, that is not true.”

They are now working on an expansion deck, called the GoBrandon variant pack, with updated “Chance” cards that include the pandemic (which they sadly now realize is still relevant), and new references to President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris, who had not yet been elected when the game was produced.

One such card in the new deck says: “You were spotted at the latest Insurrection! Go to Police Station. Luckily someone started a GoFundMyTreason for you! Collect $5,000 from every unvaccinated player.”

They recognize nothing will stay updated forever. They said they hope someday they will be contacted about updating the game for its 100th anniversary.

The game is available for sale on their website. Proceeds from the sales of the game go to the National Urban League’s Housing Division.

Sommer praised the reprisal of his original game in a letter printed in the game’s instructions: “I thought it was a great idea. Since the ’70s, many things have changed regarding race relations.

“Unfortunately, the theme of the game is still quite relevant. Even after 50 years, many of the same problems continue. Race relations have not become much better.”

Media Resources

Related Video:

Media Contact:

- Karen Nikos-Rose, News and Media Relations, 530-219-5472, kmnikos@ucdavis.edu