Research team led by Charles Walker, professor of history at UC Davis, (not pictured) and Ruth Borja Santa Cruz (center), professor of history at the University of San Marcos in Peru, digitizes documents in Peru. (Courtesy/ Charles Walker)

It was a single note that reached Angélica Mendoza de Ascarza after her son Arquímedes was taken from her home by soldiers in Peru’s military. In faint cursive on a scrap of deeply creased brown paper, he wrote that he was being held at an army barracks and asked her to find a lawyer and money and any way possible to get him to a trial.

The day after Arquímedes’ disappearance in 1983, officers at the “Los Cabitos” barracks insisted to his mother, better known as “Mamá Angélica,” that he wasn’t in their custody. However, his hand-written note would play a critical role in Mamá Angélica’s years-long effort to find justice. It would culminate in the 2017 conviction of former soldiers responsible for 53 forced disappearances that included Arquímedes'.

Between 1980 and 2000, roughly 70,000 people disappeared or were killed in Peru, according to the country’s 2003 Commission on Truth and Reconciliation report. Documents, both formal and informal, were central for both piecing together a history of this violence and successful judicial proceedings seeking justice. Today, many of those documents are in danger.

Charles Walker, Professor of History, UC Davis College of Letters and Science

Charles Walker, a professor of history in the UC Davis College of Letters and Science, was recently awarded a $100,000 grant to digitize archives from three major human rights organizations in Peru. With this funding from the UCLA Library’s Modern Endangered Archives Program, Walker will partner with co-investigator Ruth Borja Santa Cruz, a professor of history at the University of San Marcos in Peru, to preserve documents that chart a history of human rights in the country.

“These archives are really endangered,” said Walker. “If the political situation changes, these organizations might be closed and maybe even burned down.”

Digitizing human rights documentation for historical preservation

The years from 1983 to 2000 in Peru are in many ways defined by terrorist attacks against the populace on one side and severe repression by Peru's government on the other. Caught between the those two forces were tens of thousands of people from rural, mostly indigenous communities who suffered illegal detentions, forced disappearances, killings and other violations of their human rights as set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the American Convention on Human Rights.

Even when this violence went officially unreported or even unacknowledged by the government, it often left a trail of documents. They could be a handwritten letter, a local investigation or even a fax sent to a state agency asking about a loved one who was taken by authorities.

Right now, three human rights organizations in Peru — Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos (APRODEH) and Asociación Nacional de Familiares de Secuestrados, Detenidos y Desaparecidos del Perú (ANFASEP), as well as Equipo Peruano de Antropología Forense (EPAF) — all hold archives of documents that are critical for understanding the 20-year period of violence in Peru. Walker and his team will lead the process of photographing and digitally storing documents from those archives.

Many of the documents are decades old. The years have taken a toll, particularly with original communications describing the violence, which were sent by fax and telex machine.

“The paper that they used at that time was a fragile paper that is sometimes a little difficult to handle. Sometimes they fall apart simply when you touch them,” said Christian Huaylinos Camacuari, a human rights lawyer and legal coordinator for APRODEH, speaking in Spanish. “That explains why it’s necessary to have them digitized and to do it in a professional way.”

The documents at APRODEH alone fill hundreds of boxes. They include closed cases of human rights trials, including some of the most important human rights trials in Peruvian history. Many of these cases were sponsored by APRODEH in Peru with international support.

Case file from the trial of former Peru president Alberto Fujimori. (Christian Huaylinos Camacuari/APRODEH)

“All of this documentation has been used in legal proceedings that have subsequently resulted in convictions in various cases of human rights violations, including of our own ex-president of the state of Peru Alberto Fujimori,” said Huaylinos.

Fujimori, president of Peru from 1990 to 2000, was sentenced in 2009 to 25 years in prison for his role in extrajudicial killings and forced disappearances. In 2023, the Peru Constitutional Tribunal ordered his release. APRODEH was one of the organizations that challenged Fujimori's release with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR).

The shifting landscape of human rights and cultural heritage protection in Peru

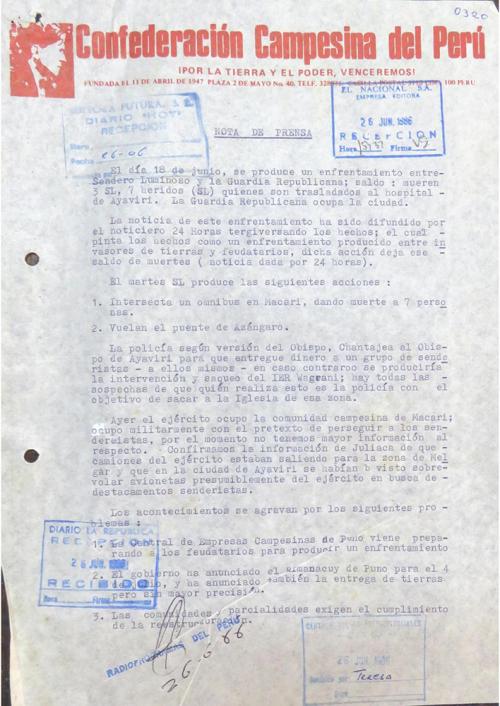

This project builds on an earlier project, also funded by the UCLA Library Modern Endangered Archives Program, in which Walker and Ruth Borja Santa Cruz digitized 40,000 documents from the Confederación Campesina del Perú (CCP). That work was completed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The CCP archive documents the history of Peru during the late 20th Century, including the growth of the radical left, the organization of major strikes and how the terrorist group “Shining Path” impacted poor and indigenous peoples. The team added descriptions in the metadata to make the digital archive of thousands of documents searchable.

These documents, which were housed in a private home in Peru’s capital Lima, are now freely available online through the UCLA Digital Library.

“When the CCP collection was published, we saw the interest and value of that material being openly accessible online to communities in Peru. We learned almost immediately afterward that CCP was a target of political repression in Peru and were relieved to know that the archive had been preserved,” said Rachel Deblinger, director of the UCLA Library’s Modern Endangered Archives Program (MEAP).

Document digitized as part of a UC Davis-led project in Peru with support from the UCLA Library Modern Endangered Archives Program (MEAP). (Courtesy/ Charles Walker)

The CCP archive is one of 112 projects across 52 countries that MEAP has supported in only its first five years. The overall goal of MEAP is to support the preservation of endangered cultural heritage and to make it freely accessible to everyone, including the communities the archive represents. Right now, the complete MEAP archive holds more than 70,000 unique documents and objects. All of them are freely available for research, teaching and non-commercial purposes.

“It is important to us that collections are documented in a way that reflects the experiences of people represented in the archive,” said Deblinger. “Having someone like Ruth Borja Santa Cruz at the center of the project, we know the materials will be well cared for and described from the community perspective.”

The new digitization project will use the same approach to protect archives that are at risk of destruction, both due to a lack of funding to maintain them and continuing threats of violence against these organizations. APRODEH has in recent years been the target of threats, including death threats against its director Gloria Cano. All three organizations fear attacks and arson that could destroy everything.

“We believe that the archival material is fundamental and is in great danger,” said Walker. “All three archives currently confront major threats and difficulties.”

Historical preservation for future research and justice

The documents are part of a complicated legacy, particularly for people who have lost loved ones in the violence. Mamá Angélica’s efforts to find justice for her son drove her work to help establish the National Association of Relatives of the Kidnapped, Detained and Disappeared (ANFASEP).

After the legal proceedings that brought her son’s killers to justice, APRODEH requested, by power of attorney, that the judiciary return Arquímedes’s handwritten letter. In a 2021 ceremony, APRODEH director Gloria Cano returned the letter to his family. Mamá Angélica had passed away only days after the reading of the sentencing.

Huaylinos said that the documents that Walker, Borja Santa Cruz and their team will preserve can also be invaluable for scholars seeking to piece together a history of the violence in Peru from 1983 to 2000.

“This documentation is important for trying to identify the possible perpetrators and, most importantly, to identify the victims and facts, who many times have been denied by the Peruvian state,” said Huaylinos. “In the cases when there were convictions, I’m convinced that those stories of horror, of suffering, of pain were converted into stories of hope, that despite the years and despite everything that was suffered, justice was found.”