Acres of asphalt parking lots, unshaded roads, dense apartment complexes and neighborhoods with few parks have taken their toll on the poor. As climate change accelerates, low-income districts in the Southwestern United States are 4 to 7 degrees hotter in Fahrenheit — on average — than wealthy neighborhoods in the same metro regions, University of California, Davis, researchers have found in a new analysis.

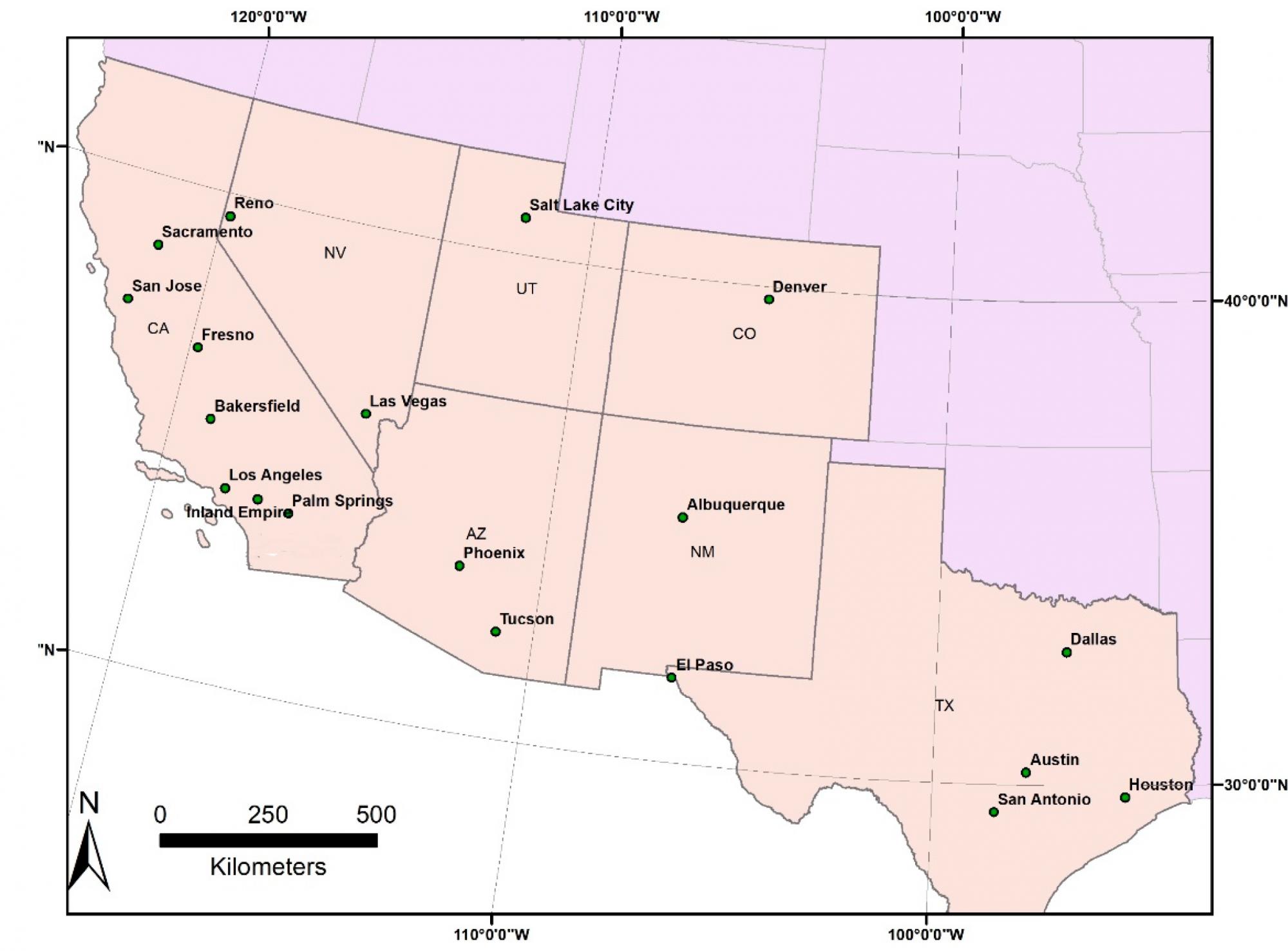

This study provides the most detailed mapping yet of how summer temperatures in 20 urban centers in California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Texas affected different neighborhoods between 2018 and 2020. The researchers found even greater heat disparities in California than in other states. The largest disparities showed up in the Riverside and San Bernardino County urban areas.

The unequal impact on Latino communities was especially apparent, the authors said. In Los Angeles on a hot summer day, for example, the most heavily Latino neighborhoods were 6.7 degrees hotter than the least Latino neighborhoods.

“This study provides strong new evidence of climate impact disparities affecting disadvantaged communities, and of the need for proactive steps to reduce those risks,” said the study’s lead author, John Dialesandro, a doctoral student in geography in the Department of Human Ecology.

The authors said that lower socio-economic groups often have less access to cooled housing, transportation, workplaces and schools. Excess heat can cause heat stroke, exhaustion, and amplified respiratory and cardiovascular issues.

It has long been known that paved surfaces of urban areas absorb and retain solar radiation, increasing urban temperatures. The surrounding suburbs — with more plant life, parks or proximity to bodies of water — will be cooler, creating heat islands in the denser areas.

“There is a strong need for state and local governments to take action to mitigate heat disparities by reducing paved surfaces, adding drought-tolerant vegetation, and encouraging building forms that increase shade and reduce temperatures,” Dialesandro said.

The study was published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Co-authors include Noli Brazi, assistant professor, and Stephen Wheeler, professor, each in the Department of Human Ecology, and Yaser Abunnasr, Department of Landscape Design and Ecosystem Management, American University of Beirut.

Researchers looked at U.S. Census data for each area studied, focusing on median household income and percentage of Latinx, Black and Asian populations in each. They also looked at education levels attained. They then assessed radiant and atmospheric temperatures recorded by satellite on the warmest summer days and nights in those cities over a two-year period.

On average, the poorest 10 percent of neighborhoods in an urban region were 4 degrees hotter than the wealthiest 10 percent on both extreme heat days and average summer days, the study said.

California’s urban regions had much larger temperature differences between the wealthiest and poorest neighborhoods compared with regions in the rest of the Southwest. The greatest differences were seen in Palm Springs, Bakersfield and Fresno. The smallest differences were seen in Sacramento.

On extreme heat days, the poorest California neighborhoods in each region were nearly 5 degrees hotter, on average, than the wealthiest neighborhoods. This compares to about 3 degrees difference in average temperatures for other Southwestern cities when comparing wealthier and poorer neighborhoods.

The largest differences occurred in the Inland Empire and Palm Springs areas in Riverside and San Bernardino County, where disparities in average temperatures between wealthier and poorer differed by more than 6 degrees.

“Programs to increase vegetation within disadvantaged neighborhoods and reduce or lighten pavements and rooftops could help reduce thermal disparities between neighborhoods of different socioeconomic characteristics,” the authors said.

While neighborhoods populated by Blacks in Southern California showed some disparities in temperature — about 1 to 2 degrees, when compared with white neighborhoods — this difference was not statistically significant. Black populations throughout Southwestern metropolitan areas are relatively small, authors said, meaning that findings on this demographic dimension were less pronounced.

Media Resources

Karen Nikos-Rose, News and Media Relations, 530-219-5472, kmnikos@ucdavis.edu