Quick Summary

- Increased drought and wildfire risk make grasslands more reliable carbon sinks than trees

- Grasslands should be given opportunities in state's cap-and-trade market as long-term investment

Forests have long served as a critical carbon sink, consuming about a quarter of the carbon dioxide pollution produced by humans worldwide. But decades of fire suppression, warming temperatures and drought have increased wildfire risks — turning California’s forests from carbon sinks to carbon sources.

A study from the University of California, Davis, found that grasslands and rangelands are more resilient carbon sinks than forests in 21st century California. As such, the study indicates they should be given opportunities in the state’s cap-and-and trade market, which is designed to reduce California’s greenhouse gas emissions to 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030.

The findings, published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, could inform similar carbon offset efforts around the globe, particularly those in semi-arid environments, which cover about 40 percent of the planet.

“Looking ahead, our model simulations show that grasslands store more carbon than forests because they are impacted less by droughts and wildfires,” said lead author Pawlok Dass, a postdoctoral scholar in Professor Benjamin Houlton’s lab at UC Davis. “This doesn’t even include the potential benefits of good land management to help boost soil health and increase carbon stocks in rangelands.”

Carbon up in smoke

Unlike forests, grasslands sequester most of their carbon underground, while forests store it mostly in woody biomass and leaves. When wildfires cause trees to go up in flames, the burned carbon they formerly stored is released back to the atmosphere. When fire burns grasslands, however, the carbon fixed underground tends to stay in the roots and soil, making them more adaptive to climate change.

“In a stable climate, trees store more carbon than grasslands,” said co-author Houlton, director of the John Muir Institute of the Environment at UC Davis. “But in a vulnerable, warming, drought-likely future, we could lose some of the most productive carbon sinks on the planet. California is on the frontlines of the extreme weather changes that are beginning to occur all over the world. We really need to start thinking about the vulnerability of ecosystem carbon, and use this information to de-risk our carbon investment and conservation strategies in the 21st century.”

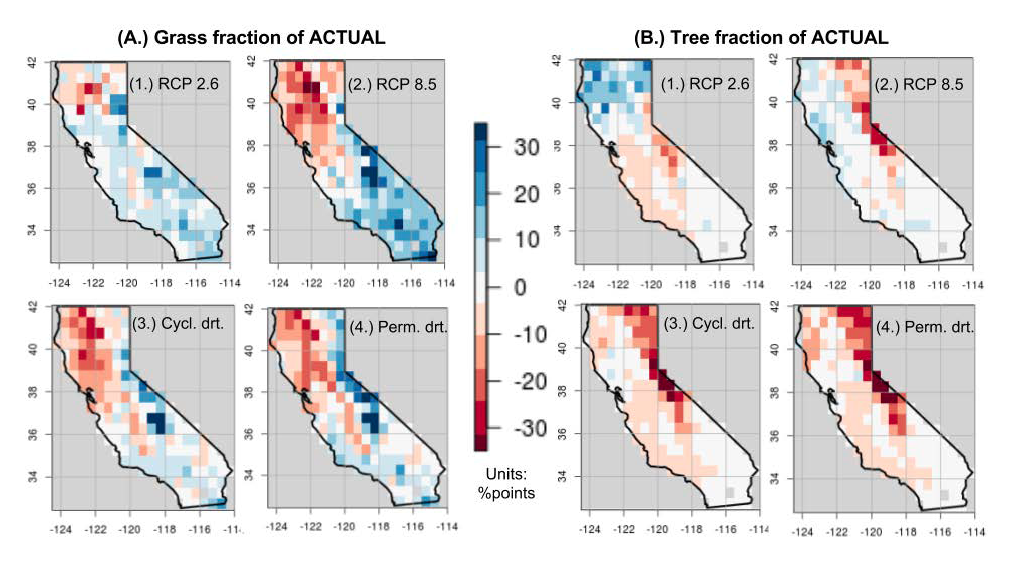

The study ran model simulations of four scenarios:

- Global carbon emissions largely stop, resulting in up to 3.06 F (1.7 C) of warming by 2100

- Business as usual, in which carbon emissions continue at the current rate, leading to a temperature increase of up to 8.64 F (4.8 C) by 2100

- Periodic drought intervals, similar to La Niña/El Niño weather patterns

- Megadrought, which can last for a century or longer.

The only scenario where California’s trees were more reliable carbon sinks than grasslands was the first one, which requires even more aggressive global greenhouse gas reductions than the Paris Climate Agreement. The current path of global carbon emissions reveals grasslands as the only viable net carbon dioxide sink through 2101. And grasslands continue to store some carbon even during extreme drought simulations.

Grassland carbon solutions

The model results can help guide “climate-smart” options for maintaining carbon sinks in natural and working lands in California. Ranchers are beginning to use innovative management approaches to improve carbon storage, which can further boost the ability of grasslands to store carbon in the future.

Trees are still critical

The study does not suggest that grasslands should replace forests on the landscape or diminish the many other benefits of trees. Rather, it indicates that, from a cap-and-trade, carbon-offset perspective, conserving grasslands and promoting rangeland practices that promote reliable rates of carbon sequestration could help more readily meet the state’s emission-reduction goals.

As long as trees are part of the cap-and-trade portfolio, protecting that investment through strategies that would reduce severe wildfire and encourage drought-resistant trees, such as prescribed burns, strategic thinning and replanting, would likely reduce carbon losses, the authors note. But the study itself did not consider in its models forest management strategies that reduce wildfire threats.

Since 2010, about 130 million trees have died in California forests due to high tree densities combined with climate change, drought and bark beetle infestation, the U.S. Forest Service reports. Eight of the state’s 20 most destructive fires have occurred in the past four years, with the five largest fire seasons all occurring since 2006.

“Trees and forests in California are a national treasure and an ecological necessity,” Houlton said. “But when you put them in assuming they’re carbon sinks and trading them for pollution credits while they’re not behaving as carbon sinks, emissions may not decrease as much as we hope.”

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation.

A Climate Change Solution Beneath Our Feet

There's too much carbon in the atmosphere and not enough in the ground. Healthy soils help flip the picture.

Media Resources

Pawlok Dass, UC Davis Land, Air and Water Resources, 413-801-6133, dass@ucdavis.edu

Benjamin Houlton, UC Davis Land, Air and Water Resources, 530-752-2210, bzhoulton@ucdavis.edu

Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu