The ichthyosaurs were sleek, dolphin-like marine reptiles that roamed the oceans while dinosaurs ruled on land. But the earliest known member of the group was a short, seal-like animal that could likely pull itself on to land. Now scanning of that animal’s skull shows that it likely fed on hard-shelled animals such as shellfish and crabs. The appearance of similar teeth in other ichthyosaurs gives insight into how these animals were evolving in the wake of the mass extinction at the end of the Permian era, 250 million years ago.

The team led by Ryosuke Motani, professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at UC Davis originally described the fossil Cartorhynchus lenticarpus in 2014. It was about a foot and half long, with a short snout, long flexible flippers and wrist bones that indicated it could probably move around on land rather like a seal.

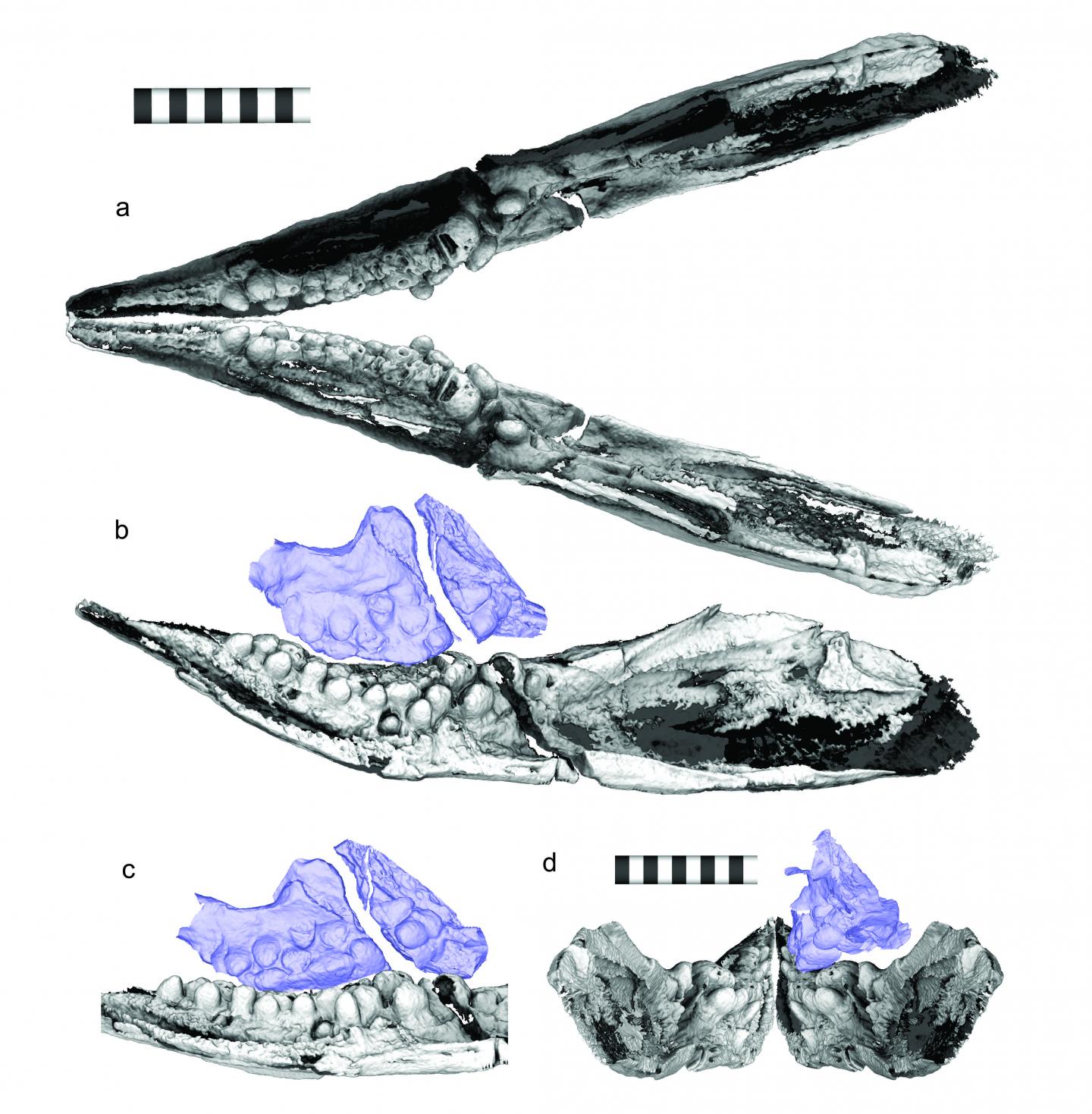

The researchers at first thought that Cartorhynchus was a suction feeder because of its short, wide snout. But using computed tomography (CT) scanning, they could see three rows of pebble-like teeth in the animal’s lower jaw. The teeth appeared to be oriented inwards rather than up towards the upper jaw.

“We described Cartorhynchus in 2014, and at the time, we thought that it didn’t have any teeth at all and was a suction feeder. But later on, researchers realized that it did have some teeth further back in its jaws,” Motani said. “In this study, we took CT scans of the fossil to see the teeth that were hidden in its skull, and we found that they had an unusual pebble-like shape.”

Sucking and crushing

These rounded teeth were in the back of the jaws, where our molars are, and were likely used to crush small hard-shelled invertebrates like snails and clam-like bivalves. Like a modern sea bream, the animal may have sucked shellfish into its mouth then used its teeth to crush them.

The teeth also showed wear and tear suggesting that even though the only known specimen of Cartorhynchus was just over one foot long, it was full-grown.

The researchers found that rounded teeth cropped up in several other ichthyosaur species, suggesting that the trait evolved independently more than once, rather than all round-toothed ichthyosaurs evolving from one common round-toothed ancestor. Meanwhile, many other early ichthyosaurs had pointed cone-shaped teeth.

These different tooth shapes springing up in different families gives us a glimpse of the world in which ichthyosaurs were evolving, said Oliver Rieppel of the Field Museum. “There were no marine reptiles prior to the Triassic,” Rieppel said. “That’s what makes these early ichthyosaurs so interesting—they tell us about the recovery from the mass extinction, because they entered the sea only after it.”

Since most sea creatures died in the mass extinction, there was a lot of free real estate, evolutionarily speaking—lots of niches for new animals to fill. It’s also likely that the repeated evolution of rounded crushing teeth in ichthyosaurs like Cartorhynchus and others was driven by the evolution of hard-shelled prey that became prevalent at this time.

Other coauthors on the paper, published May 8 in Scientific Reports, are Jian-dong Huang, Xin-xin Ren, Yuan-chao Hu and Rong Zhang, Anhui Geological Museum; Da-yong Jiang, Peking University and Chinese Academy of Science; Min Zhou, Peking University; and Andrea Tintori, Università degli Studi di Milano.

The work was supported by funds from the National Geographic Society, National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Anhui provincial government and the Ministry of Land and Resources of China.

Media Resources

Repeated evolution of durophagy during ichthyosaur radiation after mass extinction indicated by hidden dentition (Scientific Reports)

Prehistoric sea creatures evolved pebble-shaped teeth to crush shellfish (The Field Museum news release, via Eurekalert)

First amphibious ichthyosaur discovered, filling evolutionary gap (UC Davis News)