The following blog is reprinted with permission from The Commons, and the original piece can be found here. The opinion piece is written by Katheryn Russ, a professor at the UC Davis Department of Economics.

Economists are known for being a male-dominated bunch, with a rough-and-tumble, take-no-prisoners seminar culture. But if you want to scare a room full of them, talk about the economics of breastmilk.

Take the current crisis, a national shortage of breastmilk substitutes. Just using a name with “breast” in it tends to freeze up this community, which would normally be much more involved in the policy conversation. Usually when a crisis in commodity markets hits economists all over the country line up to opine for the press. In this case, you can hear a pin drop among most economic researchers.

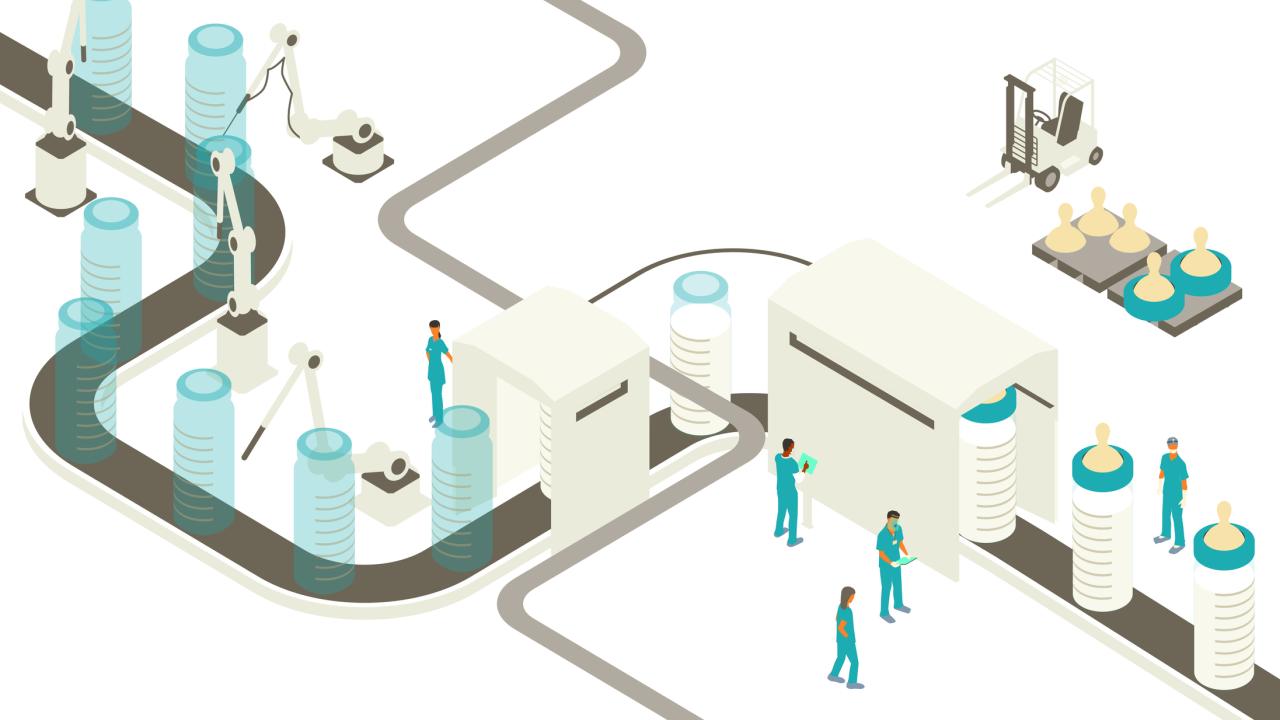

And yet we have to talk about it. Especially economists. Because the scope of the crisis is in no small part our fault. We have neglected nursing parents in economic policy, and we have turned a blind eye to the political economy of breastmilk. We have forgotten that the breast is the world’s shortest supply chain. Ensuring the resilience of this supply chain is important. It requires a wholesale shift across a number of policy spheres, but also taking on some powerful lobbies.

Start with the basics. How many babies depend on infant formula as a primary food source?

About 3.7 million babies were born in the United States over the last year. Although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that babies consume only breastmilk until they’re 6 months old, just about half do so through the first 3 months, and one-quarter through 6 months. The AAP recommends that infants continue to receive breastmilk until at least 1 year old, but nearly two-thirds do not. Simple accounting means that nearly 2.5 million infants who drink formula are vulnerable to supply shortages.

From an economist’s point of view, the current shock affecting infant formula production in the U.S. is akin to a financial crisis: It is not out of the blue, and is the sort of thing one can expect eventually to happen again. Large-scale contamination—bacterial or otherwise—and other manufacturing defects are always a risk, one that parents and policymakers may hear little about amid the barrage of formula marketing and lobbying.

The health benefits of breastfeeding are well-established. What can the U.S. do to strengthen and protect its most precious supply chain? We spend an immense amount of time thinking about industrial supply chains, so why not human breastmilk?

It is important to begin by not moralizing the costs and benefits. Not all birth parents can provide breastmilk. About 1 in 8 experience disrupted lactation or early undesired weaning. Others may suffer from post-partum conditions or unresolved sexual trauma. Breastmilk substitutes are vital in these cases and parents should not be pressured or harassed when they use them.

Yet it is safe to say that for the vast majority of babies and parents, America could do a much better job of supporting families who want to express milk rather than buy it. Globally, we rank in the bottom fifth of countries for breastfeeding rates at 6 months.

Letting parents down

A combination of institutional and healthcare failures has let down many parents, particularly people of color. Breastfeeding isn’t always simple, it usually needs to be taught, and nursing parents need support. The healthcare system often falls short. Parents don’t always get good advice, or have to chase down over-scheduled lactation consultants. Here, economic researchers and policymakers need to step outside their disciplinary siloes and listen to the public health community.

Birthparent biology is not generally welcomed in the workplace. In many professions, it would be a practical, humane choice to formalize ways to safely keep babies closer to a nursing parent or allow more remote work. In others, it would be compassionate and economical to create clean spaces and generous break policies for parents to pump breastmilk. Federal labor policies should support employers tackling these issues, and support adequate leave like in Canada.

A fierce political environment

The situation we face is no accident. Concentrated pools of wealth among big infant formula producers and a world awash in milk powder from dairy farmers struggling to survive gyrations in commodity prices generate a tough policy environment. Public health advocates need a bigger voice in public health policy on breastfeeding, but it’s hard to compete with lopsided financial resources and policymakers who are bombarded by industry lobbying or listening to experts who either belong to an institution receiving industry sponsorship or doing research that receives it.

The Biden administration’s announcement of its intentions to support breastfeeding abroad is promising, but will go nowhere without a serious examination of our trade policy. The U.S. beats up on developing countries that try to restrict aggressive marketing techniques in arcane committee processes at the World Trade Organization, pushing Thailand to weaken domestic regulation, for instance. U.S. government and industry players fight to narrow the scope for national regulation by manipulating international food safety standards. Provisions on e-commerce in trade agreements are not keeping up with the realities of predatory digital marketing and may ultimately ensconce them forever through regulatory neglect.

Tackling these challenges is not for the faint of heart. In 2016, the World Health Organization introduced recommendations to prevent misleading formula marketing practices, angering producers. A new analysis shows how industry stakeholders later began to lobby on legislation that would restrict funding for WHO. They were not alone. They found partners in a coalition targeting U.S. appropriations processes and U.S. positions toward WHO operations. This became what seemed like a steady drumbeat of lobbying throughout the government, possibly as an attempt to undermine American confidence in the scientific expertise of the world’s premier health agency not long before the pandemic hit. They demanded a dismantling of WHO’s screening protocols for commercial conflict of interest when industry wants to contribute its take on WHO operations and health recommendations.

Clearly, any administration taking the steps needed to support breastfeeding will have to brave the wrath of this political economy. To find the motivation and resolution to do it, look no further than the parents who right now are wondering how secure their baby’s food supply is. This is not a partisan issue — whether you support “life” or “choice,” we all can support birth parents. And more economists may wish to drop their squeamishness about this vital supply chain so that we can talk about how to strengthen it.

For more of her work, you can access Katheryn Russ' website here. You can find information on her latest paper on this subject here.

Media Resources

Media contact:

- Karen Nikos-Rose, kmnikos@ucdavis.edu